Samantha Cross is better described as a poly-geek, soaking up as much information as possible in order to better appreciate the things she loves. An historian and archivist, she’s a fan of comic books, movies, music, and television, never shying away from talking about or analysing pop culture minutiae on her website The Maniacal Geek. She’s also the host of That Girl with the Curls podcast where she takes the written word and voices it with her dulcet tones whether it’s in the company of friends or special guests. Find her on Twitter as @darling_sammy

As a global consumer culture one of the first things we’re introduced to is media. Television, books, movies, and music all contribute to how we perceive and relate to the world around us. The Modern Age of comics has seen the deconstruction of superheroes, the rise, fall, and rise again of comic book movies and television, and the elevation of geek culture. It is gratifying to see that one of the biggest hot button topics coming up whenever new movies, television show, or comic book comes out are representation and visibility.

We want to see aspects of ourselves in the media we consume but it’s painfully clear that Hollywood and media in general skew towards the straight, white male demographic. Denying anyone who isn’t part of the preconceived audience doesn’t just eliminate them on a visual level, it eliminates their voices and stories that could be told from the perspective of women, people of color, and the LGBTQ community. This paints an inaccurate picture of our society, with many demanding change. Hollywood has taken some sluggish steps forward, but a Renaissance of representation has occurred in comic books, at least in the smaller publishers. Marvel and DC Comics have made some strides forward, but it is mainly publishers like Dark Horse, Image, IDW, and Boom! Studios -freed from decades worth of continuity – where stories are allowed to flourish under creators actively concerned with making their comics relevant to modern readers. One of those books is Saga.

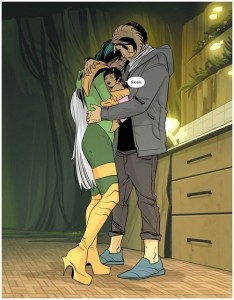

In Saga, Alana and Marko, lovers from warring worlds, flee the war, marry, and have a child, Hazel, who narrates the story of her family as they’re pursued by her parents’ peoples as well as robotic royalty, bounty hunters, ex-fiancés, and journalists across the galaxy. That’s as simplistic as the explanation gets without going into the complexities of the story, but suffice it to say that writer Brian K. Vaughan (Runaways, Y: The Last Man, Pride of Baghdad) and artist Fiona Staples (Mystery Society, DV8: Gods and Monsters, Archie) purposely set out to make Saga a book without limitations and, by their own admission, difficult to adapt.

First released in March of 2012 by Image Comics, Saga has since received as much critical acclaim as it has controversy. It should surprise no one that the bulk of the controversy concerns the art, which is understandable since comic books are, first and foremost, a visual medium. For all of the critical analysis of Saga’s narrative through Vaughan’s writing, it’s Staples’ art that grabs our attention. The fully realized sci-fi/fantasy landscape of war, sex, magic, technology, and family is as much a product of Staples’ imagination as it is Vaughan’s scripting. The result of the two creators working at the top of their game is exactly why Saga has received multiple awards and accolades. To date, the book has won six Eisner Awards, six Harvey Awards, and the first volume of the trade paperback won the Hugo Award for Best Graphic Story. The collected volumes have consistently landed on the New York Times Best Seller list where the recently released Saga: Deluxe Edition, Vol. 1 currently sits at number nine.

Vaughan’s writing on Saga has received high praise, especially from this author, for his criticisms of art, war, and media, much of which stems from what John Parker of ComicsAlliance refers to as Vaughan’s examination of the anxieties of post-9/11 America where the genre serves as “the delivery system to explore significant real-world issues.” Interestingly enough, Saga is one of the most diverse books regarding gender, race, and sexual orientation but never brings attention to it because, in the world of Saga, these aren’t issues.

Vaughan is certainly no stranger to casts of characters with a high female count. Saga continues this predilection, sporting an ensemble cast of at least seven female characters, compared to the roughly four or five male characters that appear. The diversity of race and sexual orientation, however, is where Saga earns major points with readers. While both Vaughan and Staples have pointed out that race and skin color have no correlation in Saga, Staples was instrumental in the multicultural design of the characters, creating a book where only one of the main characters, out of roughly twelve, could even be considered white (Bounty hunter The Will). According to Vaughan at last year’s San Diego Comic-Con:

“When I was pitching to Fiona, I said, ‘I don’t care how Alana looks, but no redheads. There’s a glut of redheads in comics.’ And Fiona was like, ‘Well, she doesn’t have to be white either.’ And I was like, ‘Oh, right.’”

This revelation from Vaughan shows the importance of diversity amongst creative teams alongside their books. Would the story have changed if Alana was white? Probably not, but by not defaulting to white, Staples gave Saga its own default and a galaxy enriched by diversity. Said Staples:

“Representation and diversity in comics is something that’s important to me, and I also think it just makes a more realistic universe when you’re constructing a brand-new world and you want it to feel authentic. Most of the people on Earth are not white. Why would this galaxy be?” [Source: Hero Complex]

The same is true for the visibility of LGBTQ characters. Though Alana and Marko are the straight couple at the center of the story, the Saga universe is far more fluid when it comes to sexuality. Gwendolyn, Marko’s ex, is most likely bi-sexual since she lost her virginity to a woman name Velour. Upsher and Doff are journalists and a committed gay couple trying to put the truth out about Alana’s defection. And Hazel’s babysitter Izabel recently talked about her girlfriend Windy with whom she loved and lost after stepping on a landmine. Sexual orientation is not a plot point in Saga. Rather, it is always the struggle for love –whatever form it takes – amidst the tragedy of war.

When asked why he wrote so many strong female characters, Joss Whedon famously answered, “Because you’re still asking me that question.” The same is true for Saga. We still have to keep pointing out just how diverse it is because there’s a dearth of comic books like Saga for readers interested in anything other than what mainstream publishers think is “diverse”. Thankfully, more comic books are beginning to emerge in the same vein as Saga, giving readers a playground of characters where they can see themselves without having to rely on surrogates due to lack of options. I’d like to be able to say things will change as time goes by, and I’m confident it will, but for now we’ll have to rely on Brian K. Vaughan and Fiona Staples to continue delivering in their gorgeous, poignant, and heart-wrenching space opera.