Panel Review 101 w/ Mr. B

Welcome to Panel Review 101 with your professor**, Mr. Braccino! Using his hyper-intellectual power of literary analysis and uncanny knack for identifying metaphors from any distance, Mr. B will take you through significant single issues, graphic novels, and any other category of comic worthy of a keen eye and critical consideration!!! For all those that believe that comics should be, can be, and often are more than just tights and onomatopoeiac fisticuffs, well, this here’s just the column for you!!!! Welcome True Believers, and let’s hope our little seminar in comics studies goes on and on and on!!!

**Disclaimer: Joey Braccino is not an actual professor, unless you count being a really, really hard-working public high school teacher as “professorial.” If that is the case, well, thank you for your kind words!!!

Today’s Topic: Captain America Comics #1

Objective: SWBAT close-read and analyze the debut of Captain America and his mighty shield!!! In addition to common points of analysis like visual metaphor, juxtaposition, and dynamism, SW consider the implications of the comics status as propaganda regarding America’s involvement in the escalating conflict in Europe: World War II.

Do Now: (Optional) Read Captain America Comics #1 (1941) by Joe Simon and Jack Kirby!

Prior Knowledge:

**See the most recent Talking Comics podcast for a more in-depth history lesson on Captain America!!!

- September 1939: Nazi Germany invades Poland, instigating a conflict in Europe that would eventually be swept together with a concurrent conflict between China and Japan. World War II begins.

- Still reeling from the Great Depression and committed to lingering isolationist tendencies, the United States stays out of the armed conflicts of the war, instead contributing indirectly to Britain’s war effort.

- A character called “The SHIELD” debuts for MLJ Comics (later Archie Comics) in Pep Comics #1 (Cover Dated January 1940). Comics publishers see the marketability of combining the new brand of superheroism (heralded by 1938’s Action Comics) and burgeoning patriotism. Despite the government’s line of isolationism, the comics community in New York City—predominantly Jewish—is well aware of what is happening in Europe.

- Comics legends Joe Simon and Jack Kirby developed an idea for a patriotic hero called Captain America. While there is still controversy regarding who created what when and for whom, it is generally accepted that Timely Comics publisher Martin Goodman approved the character and Simon and Kirby immediately got to work on what would become Captain America Comics #1.

- Captain America Comics #1 hits the stands in December, 1940 (Cover Dated March 1941). In other words, the now iconic cover of Captain America punching out Adolf Hitler debuted nearly a year before Pearl Harbor and America’s entrance into World War II.

- The series proves immensely popular, selling over one million copies a month after that initial release. For most, Captain America becomes a potent image of patriotism, self-fulfillment, and self-efficacy; for the persistent anti-war minority, the book and character is a source of controversy. Furthermore, according to Grant Morrison’s Supergods, at one point during Simon and Kirby’s run on Captain America Comics, American Nazis stormed into their studios looking for blood. Apparently, Jack Kirby—a World War II veteran in his own right by then—“rolled up his sleeves and went to sort them out.”

- As advertised in the first issue, Captain America Comics establishes a fan club called the “Sentinels of Liberty.” For just 10 cents, you could get your own official badge and membership card!!!

- The initial volume of Captain America Comics runs into the 1950s, but loses much of its luster after the immediate conflicts created by World War II are gone. The character leads various teams and appears in other series under the Timely banner, but without the Nazis and with popular interest in superheroes waning, Captain America Comics is canceled in 1954 with issue #78.

- And, of course, Captain America lives again in 1964 with The Avengers #4 by Stan Lee and Jack Kirby. From that point on, Cap becomes a primary character in the Marvel Universe in both his own eponymous series as well as The Avengers.

- In 2011, an issue of Captain America Comics #1 sold for $343,000. Ameri-Crazy!!!

Let’s take a look:

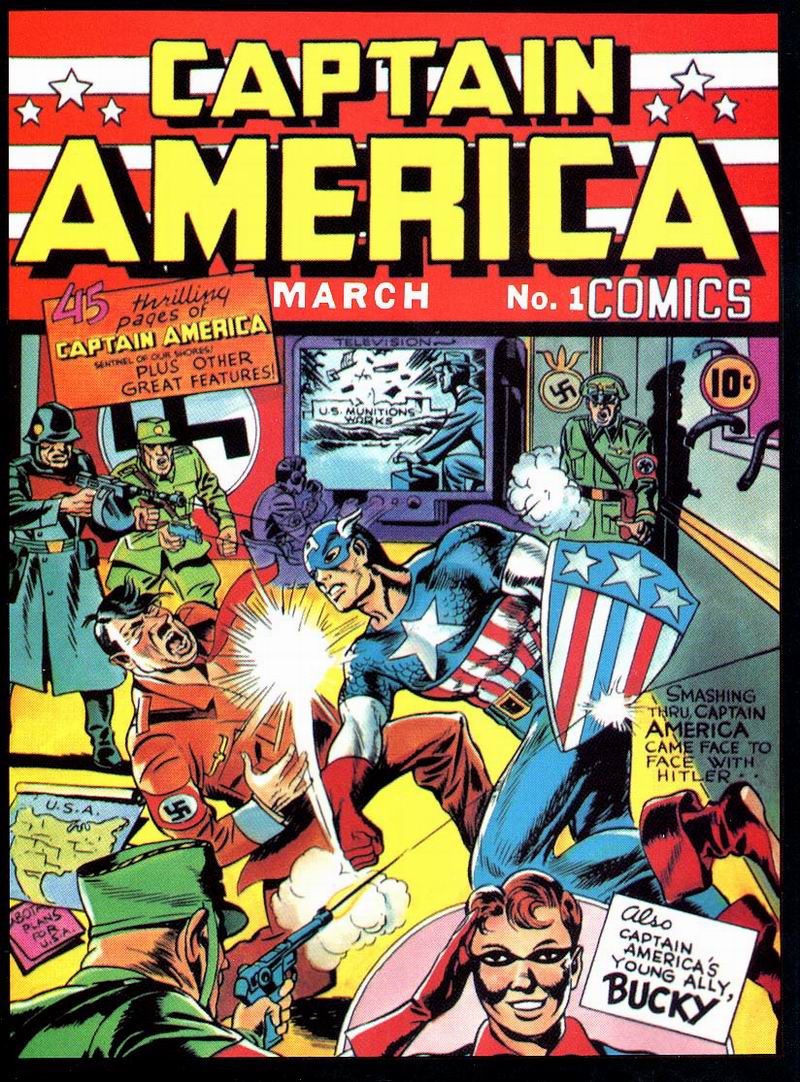

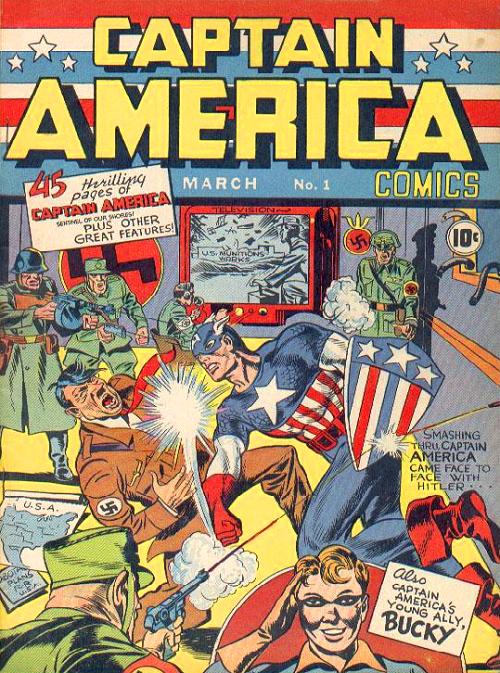

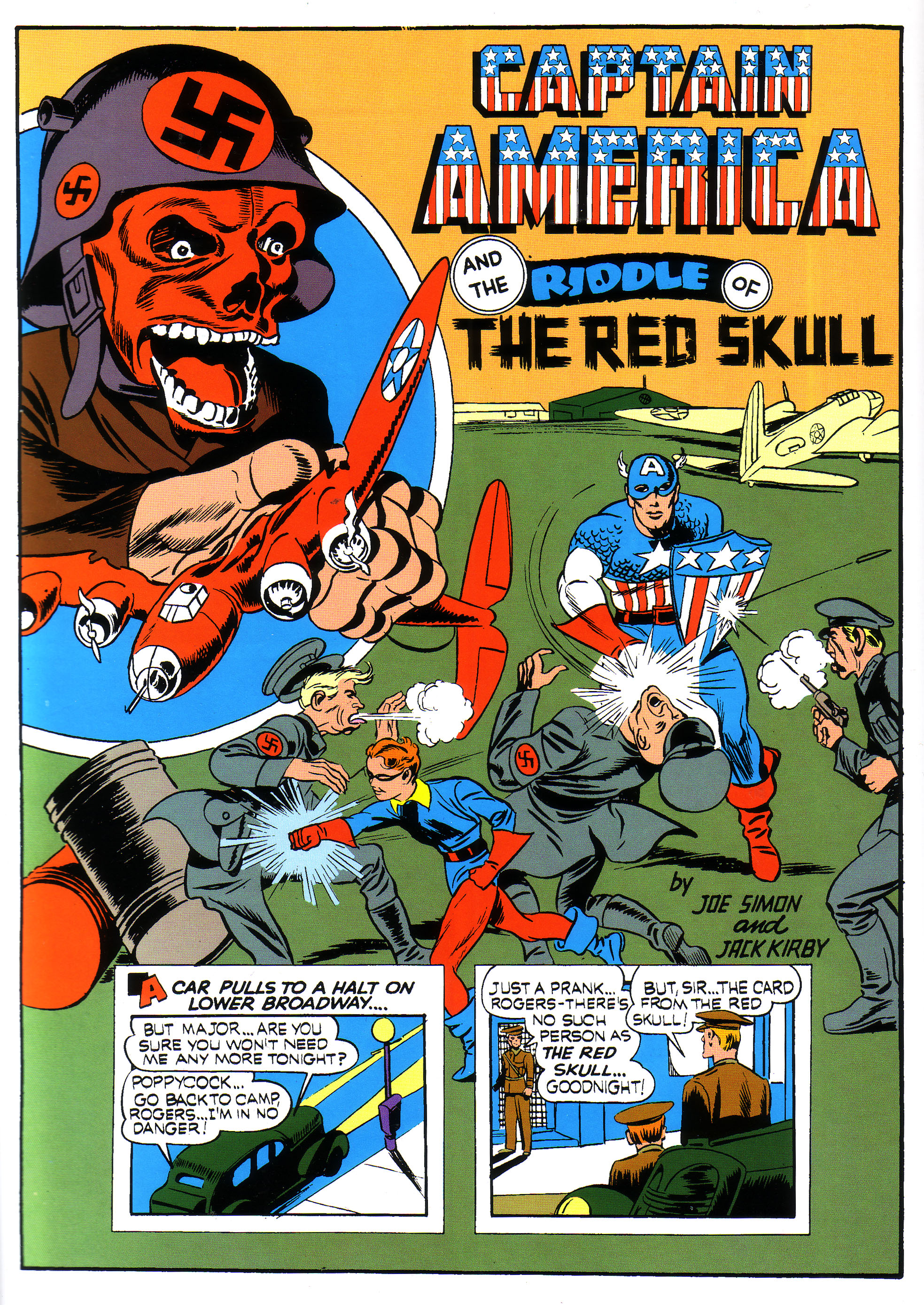

Before launching our foray into the 40+ pages of four-colored fisticuffs and superheroic patriotic semiotic analysis, let’s start with the iconic cover to Captain America Comics #1 (see above).

Part of this week’s panel review will focus on the propagandistic qualities of Simon and Kirby’s work, and the cover is the prime example of this reading. Aside from the obvious (Captain America is literally punching Adolf Hitler in the jaw—one year before the United States officially joined the war), Kirby’s artwork pushes the political agenda in a multitude of innovative ways. Kirby portrays Captain America leaping in from off the page, fist flying right through Hitler, shield deflecting the whizzing bullets every which way. From the subtle background images of an exploding US Munitions depot and “sabotage plans for USA” to the archetypical brutish illustration of the Nazi antagonists, the cover perfectly capitalizes on the fear of the American reading public. These factors will recur over the course of the narrative inside the book, but Kirby’s cover says it all: the Nazis are targeting America, and this star-spangled, shield-wielding superhero is our only hope.

The action on the cover is dynamic and invigorating, and the typeface for CAPTAIN AMERICA COMICS is just as bold and square as our titular hero’s jawline. This cover is as much a political statement as any speech or protest; America is the strongest nature, and Captain America uses that strength to fight evil (and evil is Nazi Germany). No wonder the book sold a million copies practically over night.

That propagandistic bent carries through the next “45 thrilling pages of Captain America—Sentinel of our Shores.” Over the course of four distinct stores (and one fascinating prose piece, ostensibly by Joe Simon as well), Captain America and Bucky combat Nazi spies and thugs and, in the final story, the Red Skull himself… sort of.

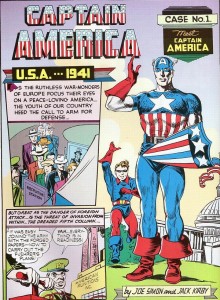

The opening splash page frames the conflict of the book as follows:

AS THE RUTHLESS WAR-MONGERS OF EUROPE FOCUS THEIR EYES ON A PEACE-LOVING AMERICA… THE YOUTH OF OUR COUNTRY HEED THE CALL TO ARM FOR DEFENSE… BUT GREAT AS THE DANGER OF FOREIGN ATTACK…IS THE THREAT OF INVASION FROM WITHIN…

AS THE RUTHLESS WAR-MONGERS OF EUROPE FOCUS THEIR EYES ON A PEACE-LOVING AMERICA… THE YOUTH OF OUR COUNTRY HEED THE CALL TO ARM FOR DEFENSE… BUT GREAT AS THE DANGER OF FOREIGN ATTACK…IS THE THREAT OF INVASION FROM WITHIN…

For a reading public sternly against joining the war effort, what better way to garner support than to pose the threat of Nazi double-agents invading our own places of business, our schools, our homes??? In the panel in the lower left-hand corner, one Nazi remarks the ease with which he “[joined] the army with forged papers.” This character speaks from just outside the panel, with only his hands visible grasping the trigger of an explosive device. Just as these Nazis were hiding in the shadows, just out of reach of our best and brightest, Kirby illustrates this Nazi terrorist outside of our view. The rest of the splash is dedicated to a brawny, burly, robust Captain America waving to the reader, standing in front of a waving America flag atop the Capitol building. While the strapping Captain America is standing firm in the foreground, a nimble Bucky—Cap’s kid sidekick—leaps in from behind, exhibiting the youthful energy and vibrancy that we need to defend!!!

Turn the page and the Nazis succeed: the munitions depot explodes in a torrent of brick and smoke and debris and “THE RESULTING WAVE OF SABOTAGE AND TREASON PARALYZES THE VITAL DEFENSE INDUSTRIES.” In actuality, the explosion paralyzes the reader. Just one panel before, Captain America and Bucky were all smiles and waves; how could we turn the page and be greeted by devastation? Well, as Kirby and Simon seem to be suggesting, that’s what happens when you ignore the creeping Nazi menace. The explosion is so powerful that the placard for next caption, “While In Washington,” is actually askew.

Simon and Kirby then give us a brief sequence in which the president—clearly FDR displayed in profile or shadow or from the nose up—suggests to a few military officials that “a character out of the comic books” would be just what America needs to solve the Nazi “problem.”

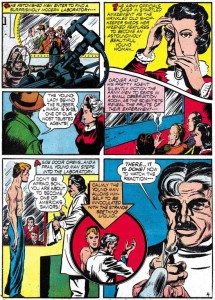

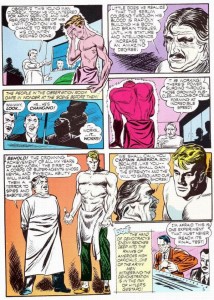

And we get the iconic sequence recognizable from the 2011 film version of the story—the trip to the Curios shop, the old lady with the gun, the doctors, the viewing room, and the scrawny Steve Rogers. Simon and Kirby don’t give us too many of the specifics that have come to be the Captain America—Brooklyn, exaggerated sickliness, vita-rays, etc.—but the foundation is there: Steve Rogers is a lanky, frail young men who tried to enlist and was rejected who is injected with a secret formula and bulks up to the ideal. Unfortunately for Professor Reinstein (get it?), the rest of the origin story is true as well; a member of the viewing party is actually a member of Hitler’s Gestapo and assassinates the good doctor before any more super soldiers could be created!!!

The narrative captions leading into the curios shop read like script to a murder-mystery: “THE DOOR SLOWLY OPENS, AND A GNARLED, BONY HAND REACHES FOR A WAITING AUTOMATIC…” The old woman guarding the entrance removes a mask to reveal the lovely features of Agent X-13, “one of [the FBI’s] most trusted agents.” Similarly, the frail Steve Rogers grows into “the crowing achievement… whose mental and physical ability will make [him] a terror to spies and saboteurs” everywhere. He becomes “Captain America… because, like [him], America shall gain the strength and the will to safeguard our shores!!!”

Once we move past the pulpy language, that idealism that Simon so desperately wants to invigorate shines through. America has become frail and timid—like the powerful imagery of the old woman or the frail volunteer—but just underneath/inside, America has the potential to fight back and become the image of strength and power.

Once we move past the pulpy language, that idealism that Simon so desperately wants to invigorate shines through. America has become frail and timid—like the powerful imagery of the old woman or the frail volunteer—but just underneath/inside, America has the potential to fight back and become the image of strength and power.

That strength and power comes out in spades as Kirby is finally let loose all over the panels. With Captain America’s newfound powers, he batters the Nazi double-agent who murdered Reinstein all over the pages. Literally. With each punch, Captain America sends the Nazi tumbling from panel to panel to panel. Kirby breaks the boundaries of each panel, demonstrating Captain America’s—and America’s more generally—ability to transcend the limits in his fight for justice. And justice is achieved brutally, as the Nazi falls into some machinery and “a million volts of electricity burn out his life.” Cap’s response? Essentially, good riddance. Serious business.

The next set of panels show Captain America once again breaking the borders as he runs toward the reader, with news headlines detailing the various spy rings and terrorist attacks that he overcomes in his defense of America!

Before the story ends, Joe Simon and Jack Kirby introduce Bucky Barnes, the mascot of the regiment at Camp Lehigh. Bucky meets Private Steve Rogers and they both admire the news clippings of Captain America’s exploits. Within one more turn of the page, Bucky stumbles upon Steve putting on his Captain America outfit and, within one more panel, becomes Cap’s partner. It was that easy!

Of course, the ease with which Bucky becomes Cap’s partner is meant to be the grand finale to Simon and Kirby’s recruitment effort, for that is really what this first chapter in Captain America Comics is meant to be: a motivating force for the reader to embrace America’s responsibility in World War II. The reader, most likely a child, has just read through Simon and Kirby’s metaphor for the innate potential to pursue justice, so what better way to end the piece than to show a young scrappy kid that the reader identifies with running off the panels alongside the Sentinel of Liberty?

While we’ve focused primarily on the first story—the origin of Captain America—there are a few things of note in the latter three.

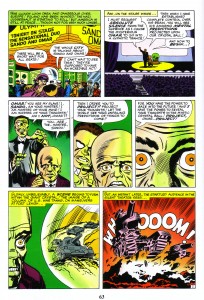

First, all of the stories follow the same general structure. Kirby always leads off with a fascinating splash page featuring Captain America stumbling upon a hyperbolic representation of the story’s antagonist. The villains are grotesque and deformed, with ragged teeth or ovoid skulls or claws-for-hand. In one corner of the splash page, ordinary citizens look on in terror. The mood is set for Simon to take us through a fairly straightforward narrative for each story: the villains murder high-ranking officials or blow up some bridge or plan on stealing some sort of information; Private Steve Rogers and Company Mascot Bucky suit up and pummel the Nazis into submission; our heroes return to base, put on their civies and pretend like it never happened when the general comes a calling. The elements are straight pulp–the freakish portrayal of the villains, the beautiful girls, the exaggerated angles, the stark shadows—but Simon and Kirby eschew romance or science-fiction or mystery for a new brand of rugged, hyper-masculine patriotic superheroism.

At one point in the final story—the one in which an industrial-magnate-turned-Nazi-spy dons a Red Skull mask and murders military officials—Captain America literally exclaims during the final fight that there’s “nothing left but the old sleep punch!” and punches the Skull’s head into a tiny pieces. A few panels later, the Skull rolls over onto a hypodermic needle and dies. When Bucky asks “why [Cap] didn’t stop him form killing himself,” Cap responds by saying he’s “not talking, Bucky!” For Captain America–for Joe Simon and Jack Kirby—the only good Nazi is a dead Nazi. This was hawkish propaganda a la the pulpy wish-fulfillment of superhero comics.

Wrap-Up:

Captain America has become one of the most iconic figures in both comicdom and American pop culture. In our current canon, he stands for the ideals of liberty and freedom, but in Captain America Comics #1, Joe Simon and Jack Kirby present us with a larger metaphor for American potential and responsibility. The frail volunteer becomes America’s greatest defender, just like every American needed to become an active participant in the fight against the Nazi’s and their atrocities against humanity. Simon and Kirby knew all the right images to include—beautiful women, grotesque Nazi antagonists, a powerful figure of hyper-masculinity, a child corollary for the reader—in order to invigorate the American public. Nearly one year prior to America’s actual initiation into World War II, Simon and Kirby’s Captain America was already fighting the enemies of democracy with shield in hand and Bucky by his side.

BONUS:

In addition to 45 pages worth of Captain America content, there is a bizarre little story at the tail-end of Captain America Comics #1 called “The Hurricane” that features a character touted as the “SON OF THOR, GOD OF THUNDER, AND DESCENDENT OF THE ANCIENT GREEK IMMORTALS.” I don’t really know how that works, but it’s a fun little romp!