The Rise of the Female Superhero: 5 Ways Comics Have Improved Female Heroes

By Sara Kern

2016 is a great year for comics. The previously restrictive doors of the comic book cultural space—which traditionally focused on welcoming straight, white men—have all but blown off. They hang by hinges made by years of regrettable practice, still present but no longer capable of keeping us out. Gender, racial, and sexual minorities are finally becoming a part of the mainstream comic world. Positive female representation is, at last, exploding.

We’re getting superheroines into pants and into movies, and we finally have icons with solo titles worth reading. It’s no wonder that there are more women in comic shops than ever before; they finally have a reason to be there.

In honor of these broken-down doors, here’s a quick analysis of some of the ways that that the “big two” have contributed to the rise of the superheroine over the last few years.

#1: They’ve started giving solo titles to female characters

#1: They’ve started giving solo titles to female characters

This is such a no-brainer. Of course superheroines should have their own titles.

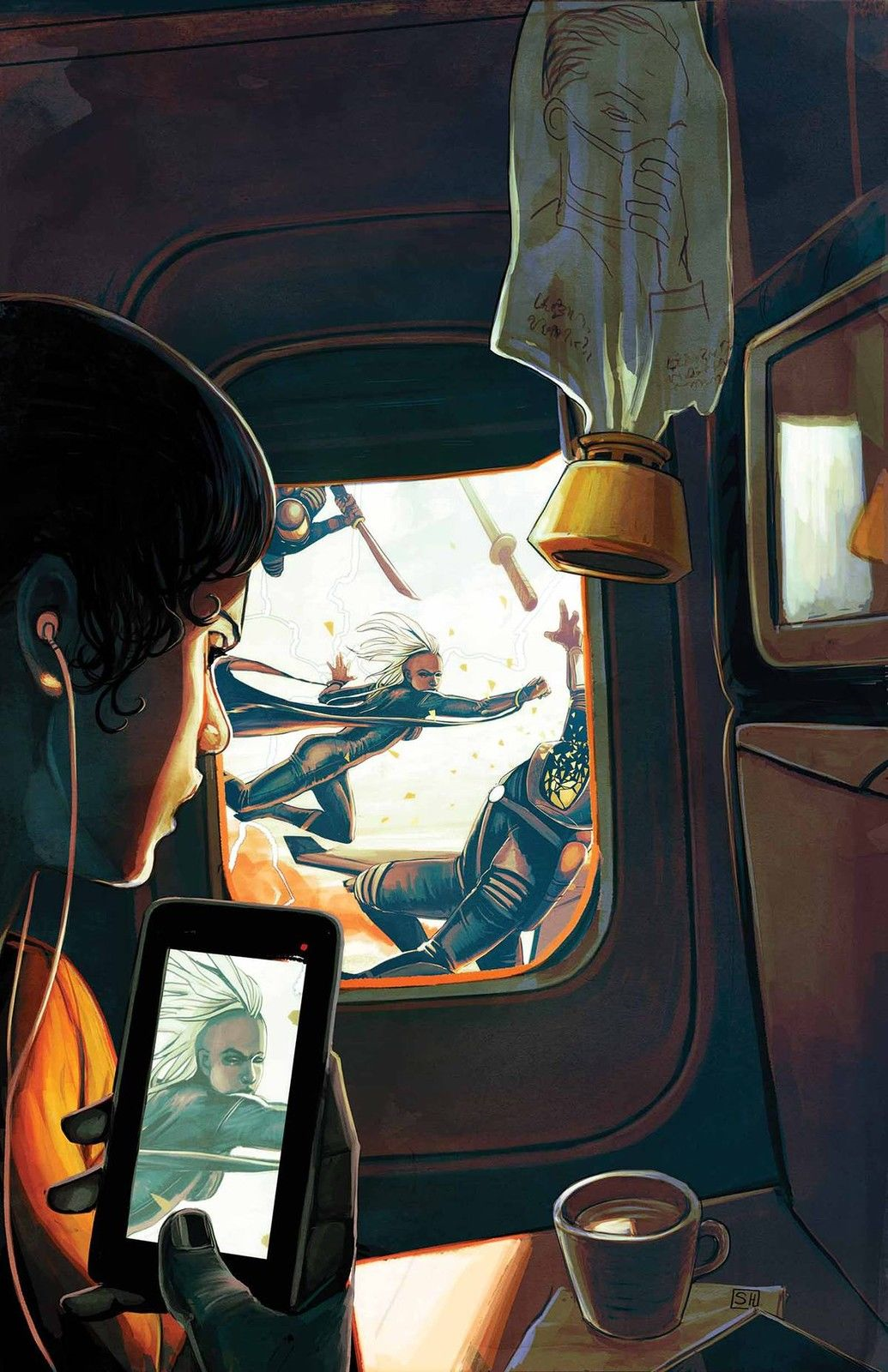

Unfortunately, until recent years the “female solo title” model was considered unsustainable. Did you know, for instance, that Storm –one of the best-known superheroes ever– had never had her own ongoing solo title until Greg Pak’s 2014-2015 run? She’d had a couple of limited series (one of which completely undermined some of the most feminist aspects of her history) but never her own title. And Pak’s Storm barely got 12-issues.

It’s all related to the outdated mainstream assumption that females are not interested in reading comics, a fact unsettled by the data, which last year indicated that female readers account for around 43% of comic book readership overall. Female readers are officially proving that “if you build it, they will come.”

I particularly love that Squirrel Girl is getting her due, and I can’t wait to see how the title develops. Ms. Marvel and Thor survived the Secret Wars, and new A-Force, Captain Marvel, and Spider-Verse titles are crowding the shelves. On the DC side we have a Wonder Woman reboot and a brand-new Poison Ivy, not to mention the ongoing Black Canary. It will be interesting to see if DC is able to catch up with the standard of heroine produced by Marvel Comics in the last few years, but any progress is promising.

#2: They’ve started to equalize the costumes and the posing

#2: They’ve started to equalize the costumes and the posing

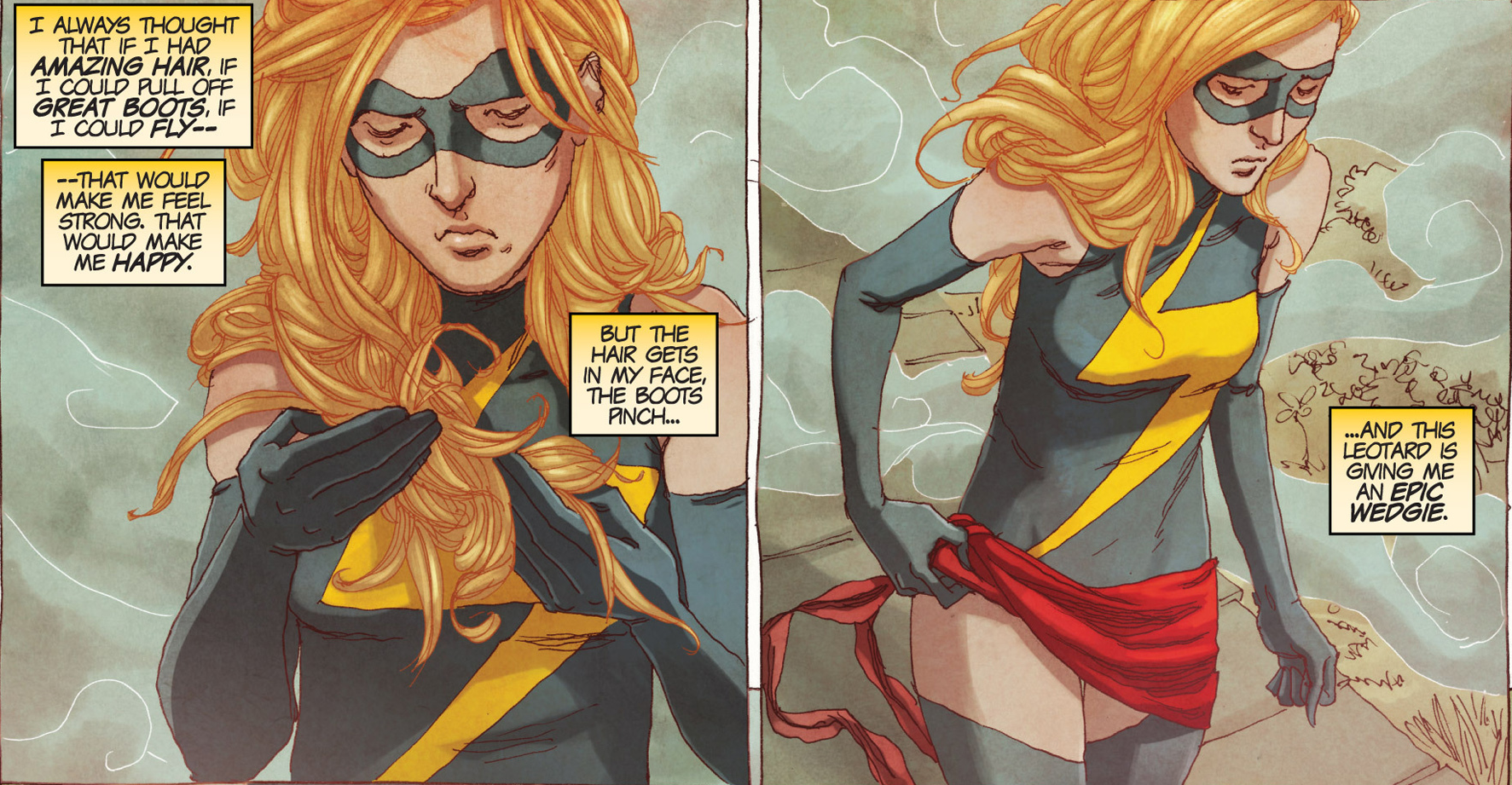

A major win for female heroes occurred with Kelly Sue DeConnick’s Captain Marvel. The new Carol Danvers series marked not only a promotion—to a title previously held by a male hero, itself notable—but also a costume upgrade. Danvers went from her racy, high-cut leotard and thigh-high boots… to pants. Like her male colleagues, Captain Marvel was given a uniform that actually appeared functional for her high-energy, incredibly physical job. It’s almost astounding that it took this long.

Spider-Woman followed suit, and this year’s Captain Marvel seems to be keeping up the trend, to the point that Danvers actually looks like she is wearing a sports bra. Female heroes have been impractically wearing push-up bras for far too long, and the trend seems to be, at last, receding.

Clearly they haven’t corrected every visual wrongdoing (and I have a lot to say about the continued costuming of DC heroines, in particular, e.g. Starfire, Catwoman, Harley Quinn, etc) but I’ve noticed a pretty awesome tendency (especially in Marvel comics) to visually de-emphasize women’s “T&A.” There was a time when the brokeback pose seemed more common than not, but, as far as I can tell, it’s disappearing.

We finally seem to be separating the female hero’s body from hypersexuality. Diana Prince was conveyed sleeping naked in Gail Simone’s run on Wonder Woman, for instance, and her nudity was not presented for consumption. It made sense within Diana’s backstory, and it wasn’t distracting.

All of a sudden there’s a lot more space for heroines to be physically strong. No longer are male heroes allowed to look like athletes, while female heroes are drawn like porn stars.

Clearly our outcry has begun to make a difference, bringing us to a place where Captain Marvel can be portrayed showering in a non-sexual way (see Captain Marvel #1), and where her biceps are way more impressive than her breasts.

#3: They’ve stopped undermining heroines’ power

#3: They’ve stopped undermining heroines’ power

Because superheroines are by definition “super,” it’s easy to get caught up in their “super” qualities and lose sight of the way that they’ve been undermined over the years. One very obvious example is their visual objectification, which has long been considered acceptable as a way of balancing “masculine” character traits (i.e, physical strength, combat acumen, etc.) with “feminine” character traits (read: T&A). But there are many other ways that female heroes have been undermined, and, lucky for us, they’re starting to be phased out.

For one, heroines of the past have rarely been allowed to be stronger than their male counterparts. There’s really great chapter about this, if you’re interested, that speaks to the way that the Black Cat finally overcomes Spider-Man in hand-to-hand combat… and then is subsequently raped. It’s a horrific example, but a regular practice: female heroes are allowed to exceed their male peers temporarily, but only if the balance is corrected immediately.

Squirrel Girl has always had a similar problem. Her powers were said to be some of the strongest in the Marvel Universe, but she was never allowed into continuity. What’s the use in having amazing powers, if your stories don’t count?

To make the power differential worse, female heroes are almost never portrayed rescuing male characters. Perhaps informed by damsel-in-distress archetypes, mainstream comics usually portray female heroes rescued by males, or, on rare occasions, male heroes being rescued by other male heroes. You could count on one hand the number of times the positions have been reversed.

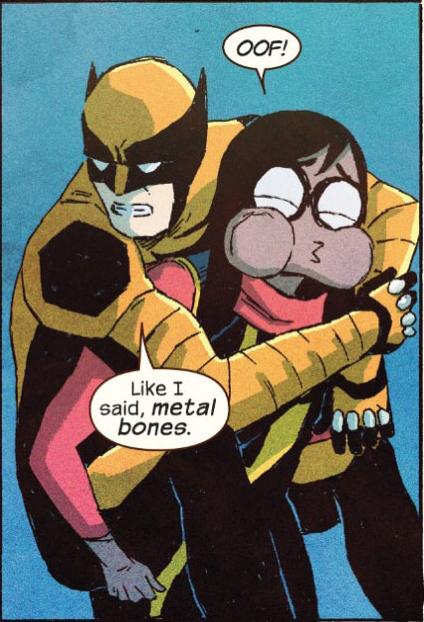

Luckily, we seem to be course correcting. The Goddess of Thunder stood up to Odinson, and Squirrel Girl has entered continuity. Ms. Marvel rescued Wolverine from the sewers just last year, and stories seem to be doing fine without overly undermining women. It’s been a long time since I read a comic where a woman was raped just to move the storyline, and that is definitely progress. Our writers are starting to be women or to see these women as human, and it’s making an incredible difference in our comics.

#4: They’ve started representing more of us

#4: They’ve started representing more of us

My favorite thing that came out of the last few years of mainstream comics is the revolutionary number of minority characters. It used to be that we had to look to underground comix for lesbian or bisexual heroes, or fully-realized and autonomous minority women, but they’re starting to gain ground in the superhero world. Pak’s run on Storm, for instance, was pretty freaking great.

This diversity is perhaps the most important thing that comics could give us.

And here’s why. There’s a moment in SNL’s recent short “The Day Beyonce Turned Black,” where two white men, cowering under a desk, contemplate the racial identities of Beyonce and Kerry Washington. “How can they be black? They’re women! ” says the first. “I think they might be both!” says the second.

“BOTH?!” his friend cries. “Nooooooo!”

Humor is a powerful social critic, and this sketch is no exception. Women are already subjugated in the media, and minority women receive dual discrimination when their gender is compounded with their racial or sexual identities. It’s a type of discrimination that, up until recently, was fully present in mainstream comics. In recent years we’ve seen an increase in both racial and sexual diversity, with Batwoman fully emerging from the closet and heroines like the Kamala Khan becoming fan favorites.

There are certainly still some problematic constructions (can we talk about the exploitation of the Harley Quinn/Poison Ivy dynamic?), but all-in-all, we’ve come a long way.

I guess my point is:

#5: They’ve started to “fully realize” our heroines

Gone are the days when female heroes existed merely as objects. Today we have backstories and personal ideals and past hurts to empathize with, including some entertaining fourth-wall risking jabs at our histories in fridges or in impractical costumes.

We no longer have to settle for superheroines who make life choices around their romantic relationships. We have racial and sexual minority figures to believe in, and to make us feel less isolated. We now have superheroines who are presented both visually and narratively with great strength. In short, we have women who are really, truly, super.

There’s a great quote from Kelly Sue DeConnick that I return to every time I think about this subject. It’s from the Women of Marvel podcast in June of 2015, where they thanked her for her service on Captain Marvel. She said,

The key to writing any character is to know them. You have to have a sense of who they are, what they want, what are their insecurities . . . I was talking to another person who asked me about writing Carol [and I said], . . . if it’s really difficult, if you’re having trouble finding her voice in your head, just write her like Chuck Yeager and don’t worry about it. And the question that I got after that was ‘Well then how am I just not writing a man in drag?’ It utterly broke my heart, because there is this notion that as women we are somehow so different that there must be some key, like ‘Oh, there’s a single expression of femininity, and this is how you write it.’ But the thing is that there are as many expressions of femininity as there are women. And they will know that she is a woman because she’s a woman. Don’t worry about it. . . . Write about what she wants, write about what is important to her, know the individual woman that you are writing.

Thank you, big two, for finally giving us heroines who are also individuals. It feels good to feel like we belong.