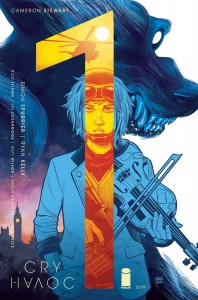

This Wednesday sees the release of one of Image Comic’s newest offerings Cry Havoc, a story that’s not just about a lesbian werewolf going to war… except it kind of is.

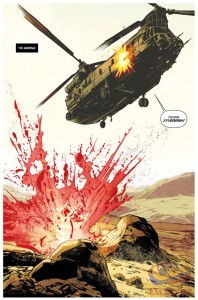

To celebrate its release, Talking Comics were lucky enough to score an interview with the book’s writer, Simon Spurrier, whose previous credits include: X:Men: Legacy (Marvel), Ghost Rider: Danny Ketch (Marvel), Judge Dredd (2000AD) and Crossed (Avatar Press).

We spoke with Si to discuss such important topics such as werewolves, East Anglian mythology, the problem of genre and ‘frilly wank’, as well as the often overlooked genius of Teen Wolf!

Talking Comics: First of all, settle a debate: An American Werewolf in London or The Howling?

Si: Very good question.

I think The Howling is great, I really respond to the notion of something secret crawling out into the open. The stuff at the end in particular is quite cogent to what goes on Cry Havoc, but for me it has got to be An American Werewolf in London. Its use of werewolves as a lens through which to see a new take on the characters and to the way it introduces comedy to the story – I’m thinking specifically of that amazing scene in the cinema with all the rotting corpses. I like the idea that you can use these supposedly quite conventional, supposedly ‘rule-abiding’ monsters, in a way that isn’t really about the monsters at all. It’s about the character, the culture, or whatever it may be. Also, Jenny Agutter, which is all I really need to say about that, so all other arguments are invalid

Talking Comics: In Cry Havoc, you really play with the traditional werewolf mythos, either through the merging of that dreaded term ‘genre’ or through the changes in time and setting. Was it difficult trying to come up with a unique approach to such a well-trodden area of mythology?

Si: As the question references, I’m no great fan of the idea of genre in general. The bottom line is that I don’t think the way we tend to taxonomise stories is particularly useful. The sorts of language we use to help us label stories are pretty idiotic most of the time, they’re not even describing the same sorts of things, let alone helping us to learn anything about a story we might or might not want to consume. So genre’s not really something I’m particularly fussed by.

The approach I take is to start from a position of a controlling idea, which is a theme, or an aphorism or a moral code. Its can be very vague or incredibly precise, but it’s the thing which is dear to me, which will define literally everything that happens in the story. It’s just a way of staying on target and not spinning off into some strange digression in terms of plot and theme. With Cry Havoc, I won’t spell out exactly what the controlling idea is because I think it will spoil the story somewhat, but it has got to do with the conflict between control and chaos, which are abstract concepts that I think define a huge amount of the way we live our lives as emotional creatures and social animals.

What’s interesting is that when you start with a controlling idea like that, you find that you can connect all sorts of vibes, motif’s and scenes even, which if you think purely in terms of fusty old genre conventions you would never put together. For instance, we are talking about Control versus Chaos; there is no reason that you cannot tell a story which relates folklore to military or to mental health, because they are all facets of the same macro theme- they’re all things that say something about that theme.

The other thing is that I’m fascinated by folklore in general. I like the kind of fiddliness of it in general; there’s that mentality and approach to mythology and storytelling that is to be able to define everything, which actually is weirdly relevant to what I was just saying about genre. There’s people who like to say there’s a myth based in East Anglia, which is based on a type of big black dog which is called the Shuck. But then there’s another one which is similar but is different because it’s called a puck or a Shagfoal or a Kelpie, or whatever the hell it is, so there’s dozens of these many localised myths. I’m not interested in saying this is one of those and this is one of those, that’s not why I’m into it. I like the idea that when you start thinking in terms of mythology and stories in general you dealing with a truly pluripotent concept. This is something around which you can base literally any theme and any secondary story that you care to name. It’s something that is remarkably powerful from the point of view of a storyteller.

So on one level, Cry Havoc is the story of a woman who gets bitten by a beast and her entire happy little existence is completely turned upside down as we know it. In an attempt to escape from it, she travels to Southern Afghanistan and is embedded within a unit of shape-shifting mercenaries, eventually getting mixed up in some supernatural/terrorist on goings. That’s a really cool story and I hope it’s one that people read and can be entertained by. But on a more fundamental level, it’s the story of a woman with chaos inside her; one who is desperately trying to escape from it and in the process learns that she might be looking at the problem in completely the wrong way. So you can see how if you describe it in these terms, people might say it has a little bit of horror, a little bit of comedy, a little bit of war or mythology and that in doing so it becomes an incongruous mess of different genres. But, as as soon as I say that from my perspective, the ‘genre’ of this story is about a character caught between chaos and control, there’s really no conflict at all between any of those elements.

That’s why I’m so proud of this story, because I really think it demonstrates very clearly that you can think of stories in a different way and not have to think about ‘breaking the rules’ of genre.

Talking Comics:Were there any previous Werewolf or Monster stories that inspired you whilst writing Cry Havoc?

Si: There’s some great stuff out there and as you would expect from what I’ve just been saying, it tends to be the less conventional takes on Werewolfism that I preferred. Dog Soldiers, springs to mind, Ginger Snaps is good as well. I guess, what I love about both of them is that they demonstrate the ‘fiddly’ details of what we like to think of as the werewolf myth, by which I mean full moons, silver bullets and all that guff, all that stuff that is not remotely as important to being able to tell cool stories about this myth than the simple thematic potential that comes from the idea of a person who transforms into some sort of predator.

At its basic level, you get to present somebody with a cool monster, you get thrills, action and drama and all the things people want, but it works so succinctly and efficiently as a metaphor for literally anything you might care to name, some of which are really profound and really deeply embedded in the human psyche. If you look at the quintessential school of folklore that surrounds werewolves, black dogs and other similar folklore, there’s this whole canon of tales and myths that relate to ‘big shaggy things’ which are half seen and roam the night, which lurk just outside the camp fire. I think they’re probably quite prototypical. I think they’re manifestations of a very basic human fear of that which cannot be seen. What makes them really sophisticated and enduring stories is that they’re not only about the monsters that lurk in the dark but they’re also what lurks inside people around us. I think we as a species are pretty predisposed towards being paranoid. If we meet someone we don’t know we’re constantly wondering what they’re hiding or what their hidden agenda might be and the idea that any one of them could quite literally be a monster is really not that far fetched on a symbolic, cultural and physical level.

But that’s all a dreadfully wanky way of thinking about it! The bottom line is that monsters are actually, really, really cool, so that’s why I embrace this stuff!

Though I might point out that the beasts, which appear in Cry Havoc aren’t technically werewolves, they’re technically Barguists, which is a particular type of Black Dog from mythology. The point made again and again in the comic is that you’re wrong to even try and ascribe names to these things. There’s something more poetic and more fundamental going on when you start thinking of monsters hiding inside people than all the frilly wank that starts to surround stuff as soon as people start creating ‘rulebooks’ for these things. Zombies are so much more frightening before somebody tells you that ‘you must remove the head and destroy the brain.’ As soon as that happens, that’s a way of making things less mysterious and less wonderful, it’s a way of describing these pretty facile scientific principles to something that is at its most profound when it is unknowable. That’s what I love about monsters and that’s what is the central dynamic at the heart of Cry Havoc, somebody that is caught between a world where everything has an answer and a name, everything is understandable and controllable, versus a world where everything is chaotic, dangerous and quiet often, deadly.

Talking Comics: You’ve previously talked about the book’s merging between military technology and supernatural mythology. Why do you think these two concepts prove to be such a potent force in terms of narrative and aesthetic?

Si: Good question! If you look at mythology and folklore as meta stories -stories that tell us a lot about the storyteller and the audience- they are attempts to explain the world, when certain things weren’t explainable. What I love about these stories and explanation is that with hindsight they are far more important because of their meaning as opposed to their truth. Most folklore is usually cautionary and always has far more meaning than the boring truth or fact.

Now, I’m a skeptic and a cynic and I don’t believe any of these wonderful tales that I love, but I do acknowledge that they are far more beautiful and meaningful than a world where we don’t have access to these stories. I think that’s sort of the way we’re going. We are forgetting what it is to take any importance and vital meaning from something we know to be false. What I’m getting at is that wherever you try to think of folklore, mythology and the supernatural and stories as units of information, they become a kind of master key, a pluripotent cell that can be mutated into any combination of theme, drama or plot that you want.

As for military stuff, that’s cool for exactly the opposite but weirdly similar reasons. As consumers of fiction we like a vicarious thrill. Hence, we’re drawn to stories of war and violence even though I think most of us acknowledge that it would be pretty fucking horrible if we were caught up in all that stuff. likewise, there’s something quite comforting to be begot from the neat, tidy, straight-line aesthetic and ‘don’t think, do as your told’ culture of military life. We live in a world where most of us feel overwhelmed by things around us, where life is currently spinning into madness, irrationality and chaos. In Cry Havoc, that side of the equation of represented by myth and monstrosity, things that are uncontrollable and untameable. The opposite force is that of control and tidiness and certainty, as represented in this story by the military and the state that gives it orders and controls people’s emotions using chemicals. My conjecture is that neither of these things are quite as simple as they may first appear and neither is as good or bad as they may first appear. Chaos isn’t purely destructive or frightening and control very definitely isn’t something you should blindly embrace, even though our present society and culture seems determined to do just that.

Talking Comics: The book has previously been described as the story of a ‘lesbian werewolf going to war.’ With this in mind, what were your main inspirations for the character of Lou and does the book comment on sexuality?

Si:Well, I guess my take on Lou is that she is somebody we all know. There’s somebody in each of our lives who’s a little like her. She’s creative, passionate, sharp, brave, and musical, but also flaky, infuriating, disorganised and unreliable. She’s the sort the person who spends her whole life being told that she needs to ‘get her shit together’ and it’s something she believes and takes to heart and feels bad about, because that’s the way our world works. We’re all supposed to want to be completely under control, completely organised and totally ambitious. That is the way society is organised. Yet we also know the world is full of brilliant people who simply do not operate like that. And so, Louise’s story is about her being pulled between those two poles: the world around her saying you need to get yourself under control, whilst a deeper internal force is constantly drawing her towards letting go and just being herself, not matter how dangerous or destructive that might be. I think it’s a really interesting dynamic that many people can relate to and the monstrous stuff, the werewolf, is really just a cipher for unleashing this bubbling passion and chaos that is inside her.

As for her sexuality, its a funny question. I always get defensive as I feel that I’ll lose points somehow if I don’t perfectly politicize why I chose to make the central character gay, which is ridiculous. Lou’s sexuality is, I’m sure cogent to the story in a thematic way, in that it says a lot about who she is and adds subtext to the story, but honestly, I could have told this story using a straight character and it would be a little different, but not hugely different. The correct answer to the question of why did I make Louise gay is that stories about gay people don’t have to be about gayness, so it just felt right. When I closed my eyes and imagined who Lou was, it felt like this was how she might live her life. Why did I make her gay, well, why the fuck shouldn’t I?

Talking Comics: You’ve previously worked for such well-known properties as Marvel’s X-Men, 2000AD’s Judge Dredd and even written several of Games Workshop’s Warhammer novels. Aside from the subject of continuity, how did your approach to working with Image on Cry Havoc differ from working on such established properties?

Si:The privilege of being a writer, particularly in comics is that you are free to work on multiple projects at once, so if your particularly privileged or ambitious you can make sure you are working on lots of different types of projects at once. Hence, there’s a whole set of gratifications, pleasures and challenges that come from sitting down to write a work for hire book for Marvel for instance, based on a character who you have grown up with than there would be to sit down and write Cry Havoc with Image.

In the former example, you have all the joy of feeling as though you are already familiar with these characters, that anyone who reads it is probably already familiar with the character and that the character often comes with decades of accumulated meaning and cache. You’ve also got an editor breathing down you neck – which by the way, can be a very good thing! With Image, there’s no editorial involvement unless you’re prepared to pay for it and you have no good will going in from readers because the readers don’t know who these new characters are.

There’s also a middle ground. I work with smaller publishers like Avatar, Boom and Titan, where there are shades of grey; elements of creator ownership, elements of creator control, with or without editorial involvement, depending on how much you want.

But, it’s a great joy to be able to work on multiple fronts in multiple different ways. I’m not sure I’d be able to put my hand up and say, which one I enjoy the most. I guess the beauty of this is that in a relatively meta way, this is totally on message with all that control versus chaos stuff I was talking about in Cry Havoc, because there is no right answer. You just want to acknowledge that this is a continuum rather than a binary state and find what works best for you. An artist tends only to be working on one project at a time, so that why I say its a real privileged to be a writer as you can do all these things side by side.

Talking Comics: And finally… who’s better: Lon Chaney Jr or Michael J. Fox?

Si: Wow! I’m gonna go for Lonster the Monster, because I love his face and I think Teen Wolf was a bit of a misstep for the young Marty Mcfly.

I do have to say there is a scene in Teen Wolf, which is truly genius. It’s the scene where he has just transformed for the first time and he’s in the bathroom. There’s a little bit of a teenage masturbation metaphor going on and his dad’s outside the door trying to get in. Now, in a lesser movie that would be the whole movie, that would be the thing where the whole story is about this kid trying to keep it secret in a kind of Peter Parker/Spider-Man kinda way. But in Teen Wolf, it’s just killed instantly when the dad comes in and he’s also a werewolf. It’s just wonderfully subverted and it proves yet again that there really is no reason that you need to approach monster stories the same way that anyone else does and always has!

Cry Havoc is released on Wednesday (Jan 27th 2016) and is written by Simon Spurrier, with art by Ryan Kelly and colours by Matt Wilson, Lee Loughridge and Nick Filardi.

Simon Spurrier was interviewed by C.J. Thomson.