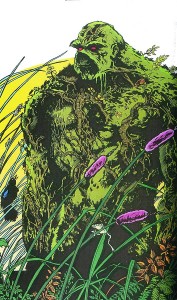

Now noted as one of the classics of the comic book form, Alan Moore’s formidable run on Saga of the Swamp Thing is something of an oddity. Filled with mythic language, psychedelic fever dreams and allusions to classical Gothic literature, the series has been correctly identified as one of the most striking and ambitious attempts at writing what could be considered a ‘mainstream’ graphic narrative. Having first read several issues in my early teens (through a dog-eared, ex-library, Trade Paperback given to me by a friend) it wasn’t until recently, when I began to re-read Moore’s entire run (of which, I am now hooked) that you begin to appreciate the unkempt brilliance that Alan Moore, Stephen Bissette and John Totleben were able to instill within what could simply be considered ‘just another pulp horror comic.’

Created in 1971 by writer Len Wein (creator of Marvel’s Wolverine) and the iconic horror artist Bernie Wrightson, the character of Swamp Thing originally debuted in House of Secrets #92, under its first incarnation as Alex Olsen, before being reinvented as Alec Holland, just in time for the character’s own solo series, which began in 1972. Originally appearing as a tribute to the pulp science fiction stories and EC horror comics of the 1950’s, Swamp Thing followed the adventures of Holland, who after being caught in an explosion, is doused with chemicals and falls into the swamp, where he emerges as his strange, monstrous alter-ego. The book was eventually cancelled, but was soon rebooted as Saga of the Swamp Thing following the release of Wes Craven’s 1982 film adaption (See IMDB.com – Swamp Thing (1982), under the stewardship of Martin Pasko, before being passed on to the then relatively unknown British writer, Alan Moore.

Under Moore’s guidance, the book soon began to change drastically from its previous form (including veering away from the comics code authorities), with Moore beginning to show glimpses of the genius that we would later be seen in such titles as Watchmen (1986) and The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen (1999).

Within the first book of the recent 2012 Trade Paperback re-release by Vertigo, reader’s can see straightaway the fearlessness and ambition of which Moore is trying to achieve within this book. Moore experiments and begins to question the very nature of Swamp Thing as a character, challenging the assumption that he is even Alec Holland at all and instead focusing on the character as a mass of sentient vegetation, which has merely assimilated parts of Holland’s consciousness; fooling itself into believing it was once human. This is courageous writing, one that not only deals with the complexities and ambiguities of identity, but also brings into question the previous stories written by Lein and Pasko, whilst moving the story and the mythology on. This is not to say that Moore completely ignores the previous books. In fact, Moore revels in the use of such previous antagonists as Anton Archane and the mainstream DC Villain, The Floronic Man (AKA: Jason Woodroe), whilst at the same time creating a deeper mythos for the Swamp Thing, threading in previous incarnations such as the original Alex Olson, within the larger tapestry of the narrative.

And what a tapestry it is.

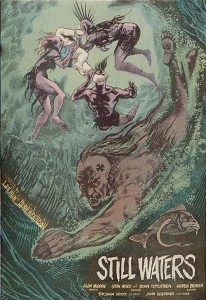

Immaculately written in a beautifully abstract, harrowing voice, Moore’s run references such classical horror writers as Edgar Allan Poe and H.P Lovecraft (of which Moore would later celebrate in the book Necronomicon). The book also plays and destabilise horror conventions and archetypes (something Moore would later famously do with the superhero in Watchmen), creating memorable stories that include zombie office workers (Blackriver Recorporations), Underwater Vampires, Radioactive Hobo’s (Nukeface) and a tragic Werewolf tale, from a distinctly feminine perspective. Furthermore, the art on display is phenomenal, with Bissette and Totleben’s work easily matching Wrightson’s intricate artistry, whilst providing their own manic and at times chaotic sensibilities to the panels.

The result, is ultimately a ‘tour de force’ from Moore, Bissette and Totleben, one that is further threaded with a distinctly american tone. By focusing on such ‘American’ themes as the Wilderness, Government conspiracies, Consumerism, radioactive/environmental breakdown and Small-town politics, Saga of the Swamp Thing touches upon a variety of different subject matter, all the while adding a specific American sensibility to the book. This use of Amerciana is particularly brilliant considering that the writer Alan Moore is from Northampton, England, a place far removed from the Louisiana swamps in which the stories mainly take place.

Saga of the Swamp Thing, hereby stands as a unique benchmark, not only for the horror genre in comics, but also for mainstream genre comics in general. Moore’s text looked to transcend barriers by offering the same humour, thrills and action as its predecessors, but merging them with many of the classical greats of the genre, as well as threading them with a tangible commentary on contemporary America.

The result is a genuinely mythic, legendary, and dare I say it, literary, comic book masterpiece.