MJ Feuerborn is an American queer activist, freelance journalist, and comics enthusiast. She writes for Women Write About Comics and Comicosity. Her comics and culture commentary can be found on her blog or on Twitter at @mjfeuerborn

Click here for the introduction to the Comics, Human Rights and Representation Week.

Comics are a medium with endless possibilities. Illustrations aren’t constrained by real world limitations, with grounded and abstract imagery allowing for the delivery of very unique messages. The addition of text — as dialogue, narration, or contextual explanations — furthers the ease with which messages are received by readers. This simultaneous presentation of text and art provides endless opportunities as both a method of storytelling and as a tool to express thoughts and concepts.

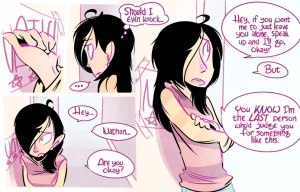

People occupying all reaches of the queer spectrum have been making use of the comics medium for decades, telling stories both fictional and anecdotal, and as a vehicle to catalogue history and promote social change. From hand-made booklets once passed out at queer events and bookstores, to the wealth of webcomics now available on the internet, the queer corner of the medium has always been largely do-it-yourself, existing outside of the mainstream comic book industry and self-sustained.

No Straight Lines, an anthology edited by Justin Hall and published in 2012 by Fantagraphics, provides an excellent look at this legacy, collecting queer comics from every post-Stonewall decade. The book starts with strips that appeared in early gay newspapers and magazines, moving through time on the pen strokes of forty years of queer struggle, celebration, and commentary, and culminates in the transition to the internet in the wake of dwindling local venues and the opportunity of reaching larger like-minded audiences.

Webcomics make up a bulk of the queer comics being done today, both in serial storytelling format and as strips. There are literally dozens of ongoing webcomics starring LGBTQIA characters or featuring queer themes, and hundreds more have been created and retired over the years as projects come to fruition. While much of this work is done for free, many queer webcomic creators support themselves through donations, or through funding sites like Patreon. A. Stiffler and K. Copeland, for example, are a queer couple who produce two ongoing webcomics as well as an array of short stories, and their readers collectively provide over $400 per comic.

But even in the digital age, queer comics are hardly restricted to the internet. Queer publishers such as Northwest Press have been steadily producing comics for years, and Prism Comics — a nonprofit organization that supports queer comics — even offers a yearly grant to help creators publish. And in recent years, creators have found plenty of new options for self-publishing, including raising money through Kickstarter, like recent successes Qu33r, Virgil, and The Young Protectors (which made nearly ten times its $14,000 goal), and allocating funds from Patreon.

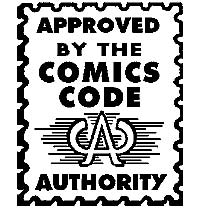

Queer presence in mainstream comics has a much less consistent history. Though once indirectly forbidden to do so by the Comics Code Authority, the mainstream comic book industry has managed to thread queer themes and LGBTQIA characters into books for decades. While the Code was fully intact such instances were rare and generally ambiguous, but as decades passed the Code’s guidelines were loosened, and subsequently rendered obsolete by companies gradually abandoning its use. There are no longer any official restrictions prohibiting the inclusion of queer characters by mainstream comics publishers.

Mainstream comics are largely populated by superhero comics published by the “Big Two” of the industry: Marvel and DC. Both companies operate on “shared universe” storytelling dynamics, meaning that all of their books take place in a single universe and star characters that have been around for decades – and the vast majority of those characters are white, male, cisgender heterosexuals. While new characters are introduced frequently, they rarely become permanent fixtures in their respective universes, coming and going on the whims of individual creative teams. For LGBTQIA characters, this is a big problem.

While both Marvel and DC have shown themselves willing to put the spotlight on their queer characters, that spotlight is temporary and is often followed by the character fading into obscurity. Marvel’s Northstar both proposed to and married his boyfriend Kyle Jinadu in Astonishing X-Men in 2012. The event received a great deal of press, but the book was later canceled. Similarly, DC’s Batwoman made headlines when Batwoman proposed to her girlfriend Maggie Sawyer in 2013, but after editors refused to allow the creative team to move forward with a wedding, the team walked off the book. Batwoman, too, was later canceled.

In fact, nearly all comics featuring queer characters at the Big Two end in cancellation. Marvel’s Daken: Dark Wolverine, starring Wolverine’s queer son, and DC’s Voodoo, starring a bisexual woman Priscilla Kitaen, among the few queer-led solo books in either companies’ history, were both canceled in 2012. Team books featuring LGBTQIA characters fair no better, as recent years have seen the cancellation of nearly every queer-inclusive team like DC’s Stormwatch and The Movement, and Marvel’s Avengers Academy, Uncanny X-Force, and Fearless Defenders. And unfortunately, the “rehoming” of stranded queer heroes in different titles after their own books are canceled is entirely at the discretion of individual writers. This typically results in queer characters disappearing for long stretches of time.

Archie Comics, another publisher with shared universe comics, has done much better than its Big Two counterparts in this regard. Kevin Keller, a gay man introduced in their comics in 2010, was later given a mini series to better establish his character, and then an ongoing solo comic in 2012. The company has remained committed to keeping Keller busy and included across their line. They have included a gay marriage storyline in Life with Archie, made Keller a superhero, and devised an alternate universe in which Archie Andrews himself dies to protect him. Not only is Keller a fully-fleshed character with his own ongoing stories and connections, he’s become a genuine cornerstone of the company’s shared universe.

But few other comics publishers employ the shared universe dynamic. This means that the comics they publish are mostly self-contained and star either original casts or characters previously established in other mediums. The potential is always there to include LGBTQIA characters, but similarly to the Big Two, those decisions are left to individual creative teams. Recent queer-inclusive successes include BOOM! Studios’ The Woods and Lumberjanes, Image’s Trees, and IDW’s Transformers: More Than Meets the Eye.

The Woods has several queer characters within its core cast, and their backstories are threaded with uniquely queer experiences that highlight the characters’ sexuality without making it their defining trait. Lumberjanes is similarly refreshing in its inclusion of a lesbian romance which is treated with the same frankness and playfulness as the cast’s frequent battling of demon foxes and river serpents. Trees’ vast cast includes two transgender characters and a bisexual protagonist, and while the language used has been problematic, the character-driven discussions on sexuality and gender are stark and honest. Lastly, Transformers proved in 2013 that even when writing for established properties, there are always opportunities to include queer characters.

Andy Mangels, while participating in the Gays in Comics panel at the 2007 San Diego Comic Con, summarized the issue of queer representation in comics well when he stated, “I discovered that in doing [comics] for so many years, that often times it’s not a question of, ‘Is it appropriate to put gay or lesbian, or bi or trans characters into something?’ it’s a question of, ‘Are the creators asking themselves to do so? Are they even thinking about us?’” Creators across the queer spectrum have tirelessly created and published their stories through independent means for decades, evolving with the times to reach new audiences. While mainstream publishers have been making selective efforts, it’s long past time for them to make a commitment as a collective to create more queer characters, and make sure those characters get to stick around.

Click here to read all of the Comics, Human Rights and Representation articles.