Maria Werdine Norris is a final year PhD candidate at the London School of Economics and Political Science. Her research is on the British Counterterrorism strategy and legislation, with a focus on nationalism, security and human rights. You can find her on Twitter as @MariaWNorris

Click here for the introduction to the Comics, Human Rights and Representation Week.

The definition of terrorism provides us with a question with no clear-cut answer. Terrorism can be understood to be a tactic, a strategy, a concept, a social or political phenomena (Horgan & Boyle, 2008). But rather than being a material fact, terrorism is best understood as a label, subject to a value judgement. As such, investigating what terrorism is invariably involves questioning how events and actors are labelled as ‘terrorist’.

For at least ten years, Islam has been associated with terrorism, with Muslims having become the new suspect community. This is primarily a result of the narrative of terrorism constructed by policy and legislation and reflected in popular culture.

This narrative makes it difficult to separate terrorism from Islam, especially in light of its emphasis on identity. As Prime Minister David Cameron stated on his 2011 speech at the Munich security conference:

I would argue an important reason so many young Muslims are drawn to [extremism] comes down to a question of identity.

The questioning of the identity of British Muslims is compounded by the official British counterterrorism strategy’s focus on the importance of British values. Extremism is defined as the lack of British values, and as a result, the promotion of British values is touted as the solution to terrorism. The situation is very similar in the US. In his book, The Muslims are Coming, Professor Arun Kundnani highlights that Muslims have been criminalised in the US due to the two dominant security approaches, the culturalist and the reformist. Culturalists locate the problem of terrorism in Islam itself whilst reformists argue that the problem lies in a distortion of the religion. And yet, both security approaches place Islam at the root of terrorism.

This problematizing of Muslim identity is not confined to Britain and the US, but reflected in events such as the French banning of the hijab and full-veil coverage, the 2009 referendum on minarets in Switzerland and the recent Anti-Islam protests in Germany. Unsurprisingly, the past ten years have seen the rise of Islamophobia and the soaring numbers of crimes against Muslims.

Into this highly charged atmosphere, enters Kamala Khan. Created in 2013 by G. Willow Wilson, Sana Amanat, Adrian Alphona and Jamie McKelvie, Kamala is a 16 year old Pakistani-American girl living in New Jersey. One night, after sneaking out to go to a party without permission from her parents, Kamala is enveloped by the Terrigen mist and emerges from a cocoon with super-powers. Emulating her hero, Carol Danvers aka Captain Marvel, Kamala becomes the new Ms. Marvel (which was Carol’s original superhero name). It is important to highlight that whilst not the first Muslim superhero, Ms. Marvel is the first one have her very own book.

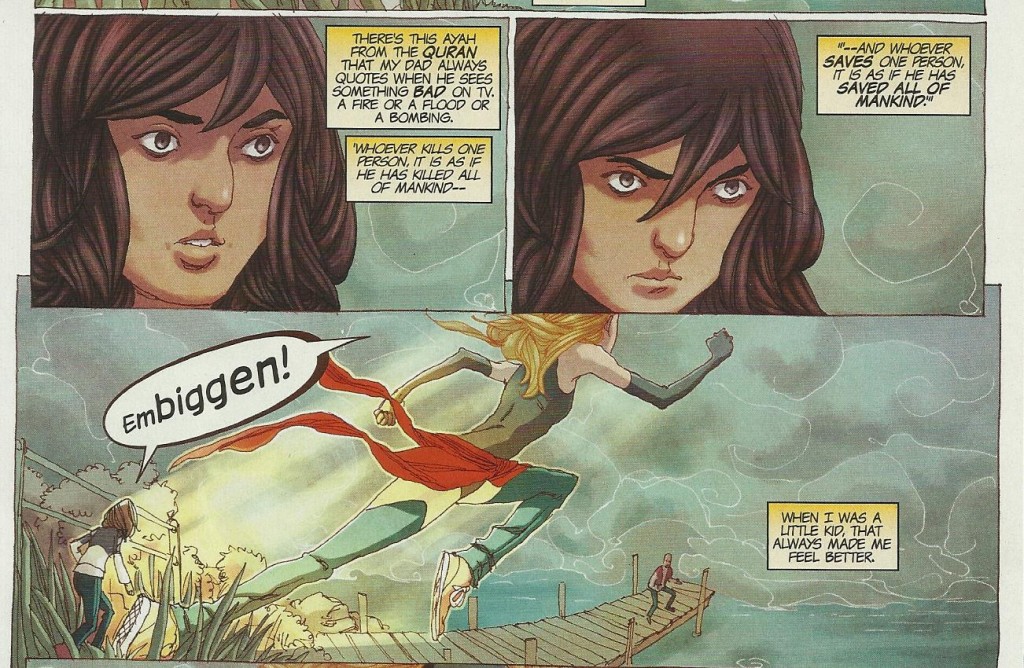

Kamala and her family are devout Muslims (her brother is actually a salafi), but although it is part of the story, Islam is not a plot point. Kamala is not defined by her religion, it is just part of who she is. In one of the books most powerful scenes, Kamala draws inspiration from words from the Quran.

The book’s representation of Islam is both accurate and respectful, and one must point out the fact that writer G. Willow Wilson is herself a Muslim and Sana Amanat, the series editor, is Pakistani-American. Speaking on the reasons behind creating Kamala Khan, Amanat said

[It’s a way] of representing a portion of the population that doesn’t really have representation in pop culture. I think what’s really important about these stories is that you’re not saying, “Hi, I’m [a] Muslim character, and this is all I’m about.” It’s sort of about the up and down, and the comical events of the day. Then, you start caring about the character [because] you normalize “the other.”

And Kamala and her family are decidedly ‘normal’. Kamala is a nerd who spends her time writing fanfiction, her mother is concerned about her family’s move to America and her dad – like most dads – is typically overprotective. Her brother’s more conservative views are presented affectionately. The scenes at the mosque are authentic and also subversive. When her parents, worried about her behaviour, order her to speak to Sheikh Abdullah, both Kamala and the reader expect a stern telling off based on expectations of female behaviour and the Q’uran. Rather, what we get is a show of love and respect from Sheikh Abdullah, who whilst concerned, loves and believes in Kamala.

As such, Kamala Khan disrupts the narrative that problematizes Muslims and is a rare example of positive, successful and nuanced Muslim representation in media and popular culture. Kamala Khan is important. But not only that, she is also popular. Ridiculously so. Marvel Publisher Dan Buckley recently said in an interview:

We’re not holding on to critical darlings right now. Ms. Marvel is a legitimate top-selling title for us in all channels.

In late Summer 2014, Ms. Marvel #1 went to a historical 6th printing. Only a handful of other comic books have ever reached a 6th printing. Ms. Marvel #1 is now on its 7th printing. Ms. Marvel: No Normal, collecting the first five issues of Kamala’s story, topped the New York Times bestsellers list. Ms. Marvel is also Marvel’s bestselling comic book in the digital market. Critically, the book is also a success, having won and been nominated for almost every award in the comic book industry, including multiple nominations for the prestigious Eisner award.

More than just a success story for the comics industry, Ms. Marvel is also a powerful tool in the quest towards visibility. As such, she is also a tool in combating hatred and prejudice. Sometimes quite literally. In San Francisco, an organisation called the American Freedom Defence Initiative, a hate group according to the UK government, paid for a series of Islamophobic bus adverts equating Islam with Nazism. Little did they know that they ads would be covered by graffiti calling out racism, featuring none other than Kamala Khan.

More than just a success story for the comics industry, Ms. Marvel is also a powerful tool in the quest towards visibility. As such, she is also a tool in combating hatred and prejudice. Sometimes quite literally. In San Francisco, an organisation called the American Freedom Defence Initiative, a hate group according to the UK government, paid for a series of Islamophobic bus adverts equating Islam with Nazism. Little did they know that they ads would be covered by graffiti calling out racism, featuring none other than Kamala Khan.

Ms. Marvel has been hailed as the most important comic book at the moment. Ms. Marvel is not just a symbol of change in comics, but also a symbol of hope for representation. This book counters the relentlessly negative portrayal of Muslims in media and popular culture and its success makes it clear that diversity matters. It is then not a stretch to say that Ms. Marvel promotes human rights, for it makes the invisible not just visible, but loved. Kamala Khan thus stands proudly and tall against the current narrative of terrorism. And she does all this whilst being a Muslim teenage nerd in a cape.