Carolyn Cocca is Associate Professor in the Department of Politics, Economics, and Law at the State University of New York, College at Old Westbury. She is the author of Jailbait: The Politics of Statutory Rape Laws in the United States (SUNY Press), and most recently, of “The Brokeback Project: A Quantitative and Qualitative Analysis of Portrayals of Women in Mainstream Superhero Comics, 1993-2013”, “Negotiating the Third Wave of Feminism in Wonder Woman” and “Re-booting Barbara Gordon: Batgirl, Oracle, and Feminist Disability Theories” in ImageTexT. She teaches courses on U.S. politics, civil liberties and civil rights law, and the politics of gender and sexuality.

If you ask someone to name a superhero, that person will probably name Superman, or Spiderman, or Batman, or Captain America, or Wolverine. The word “superhero” pretty much assumes that the hero in question is male, and white, and heterosexual, and able-bodied. That’s why many people clarify when they’re talking about “female superheroes” or “black superheroes” or “queer superheroes” or “disabled superheroes.” That’s why Microsoft Word keeps trying to tell me that “superheroine” isn’t a word by underlining it in red.

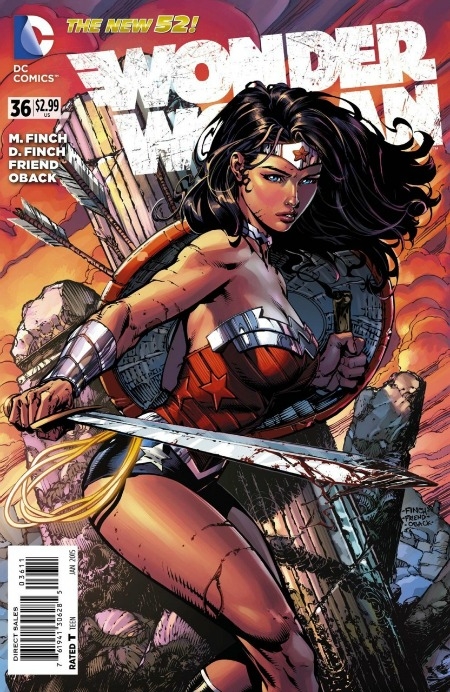

If you ask someone to name a female superhero, that person will probably name Wonder Woman. There are a number of reasons why she is quite special, and we should celebrate her recognizability and the way in which her very name is shorthand for a super-capable woman. Having said that, there are certainly aspects of the ways in which she has been portrayed since her creation in 1941 that should give us pause and push us to advocate not only for more representations of heroic women, but also more diverse representations of heroic women.

Wonder Woman isn’t special because she’s a superpowered hero fighting for truth and justice. Batman and Superman were both doing that before her, and they still do. What’s special is that she does these things through a female body. In a world in which women have been treated unequally by law and by custom for far too long, she demonstrates that heroism and intelligence and strength and leadership are not male traits; rather, they are human traits that can be performed by anyone. Or, as her portrayal also cannot but imply, they can be performed by someone who is white, nearly nude, attractive, heterosexual, and able-bodied.

Wonder Woman’s woman-ness, in other words, is what makes her special. Her creator, lawyer and psychologist William Moulton Marston, subscribed to the idea that not only were women equal to men in capabilities, but were in fact superior to men in terms of their capacity for love and aversion to violence. His Wonder Woman is fashioned by her mother from clay, given life by the gods, and raised in an all-female Amazon society. She chooses to come to the U.S. during World War II to teach peace and equality. Using diplomacy first, and force only if necessary, she and a group of college women repeatedly question and subvert gender inequality, and tout the virtues of love and of human rights. This performance of traits and actions constructed traditionally as “feminine” and “masculine” highlights the instability of binary categories and creates space for more fluid gender possibilities.

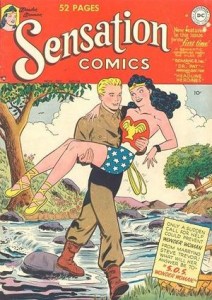

Such fluid portrayals of gender were resonant at the time, particularly as women were exhorted into “men’s” work for the War effort. But this did not survive the postwar “cult of domesticity.” From Marston’s death in 1947 to the late 1960s, Wonder Woman’s portrayal was quite different—hyper-heteronormative. Her costume shrunk; her eyes and hair grew; her interest in romance intensified. Instead of battling fascism and crime with other women, she battled fantastic monsters alone, or with littler versions of herself, “Wonder Girl” and “Wonder Tot.”

The book changed direction again from 1968 through the mid-1980s—as the Second Wave of feminism was making legal and cultural gains. Stereotypes of gender, sexuality, class, and race manifested through the overarching plot: Wonder Woman gave up her powers to keep her boyfriend’s attention. Then he died. She bought a fashion boutique, dated a series of men and cried over them, and trained in martial arts under an elderly Asian man named I-Ching. The creative team saw this as feminist in that she would be a self-reliant business owner, not dependent on superpowers. Some fans and many feminists didn’t see it that way and lobbied to have her powers returned. They were, but many of the 1970s and early 1980s stories showed the character in a smaller costume and more suggestive poses as she battled equally curvy women. Some stories stereotyped feminism as anti-male rather than pro-equality, indicative of misunderstandings of and backlash against the civil rights movements.

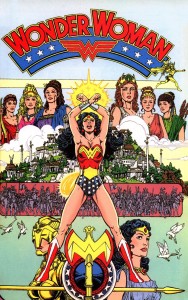

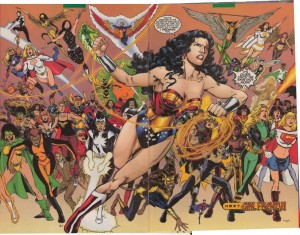

No one wanted to write Wonder Woman when DC Comics rebooted all of its superhero titles in 1986. Superstar writer/artist George Pérez volunteered, along with the title’s first female editor Karen Berger. Their portrayal harkened back to those of creator Marston’s. Pérez says he purposely drew her as more “ethnic” and drew the Amazons as more racially diverse, and implied that some Amazons were in romantic and/or sexual relationships with each other. Sales were high and fan letters were enthusiastic about the book’s politics.

But as conservative politics clashed with liberal identity politics in the early to mid-1990s,

many mainstream superhero comic titles began to display a hypergendered backlash to the gains of the feminist movements. The next writer, William Messner-Loebs, worked with a number of artists on the title, but it was the last one, Mike Deodato, who garnered the most attention. Deodato later described his approach to Wonder Woman,

“I kept making her more … um … hot? Every time the bikini was smaller, the sales got higher.”

He drew more violence as well. The combination of a well-written story, sexualization, and increased bloodiness apparently appealed to the mid-1990s comic fan base, which due to a variety of factors had shrunk and homogenized; it became mostly male, white, heterosexual, and adult.

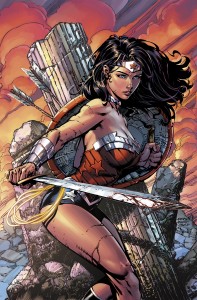

It seems as if there was such discomfort with the portrayal of strong female comic characters that their threatening nature had to be counter-balanced with exaggerated sexualization to remind us that women should be objects to be acted upon rather than identified with. Male superhero characters are idealized in terms of their musculature, certainly, and tend to be posed facing front and looking strong. Female superheroes, by contrast, tend to have their curves rather than muscles accentuated, and to be posed sideways or twisted to further draw attention to the curves.

But there has been pushback to these portrayals, perhaps indicative of the inroads of the Third Wave of feminism’s emphasis on intersectionality. In the 2000s, Wonder Woman writers such as Phil Jimenez, Greg Rucka, and Gail Simone wrote the character as clearly feminist, showcasing her diplomacy, her compassionate approach, her strategic thinking, and her physical strength. Jimenez, who himself drew the character as sexy but not sexualized, had the character found the Wonder Woman Foundation to promote equality for all. All three developed diverse supporting casts as well. After their runs, and as part of an industry-wide trend, sales started to decline.

In 2011 as in 1986, DC Comics again sought to increase their sales by rebooting their superhero comics.

The new writer and artist were Brian Azzarello and Cliff Chiang, and initial sales and reviews were quite positive. The art shows Wonder Woman as a powerful and confident subject. She is true to her mission of compassion and love, and over time, becomes a leader of those around her. But her backstory has been rewritten such that she is the offspring of Zeus rather than fashioned from clay; the Amazons are not peace-loving and pro-equality, but rather, rapists and murderers; she is quicker to threats and violence; and her decades old arch-enemy, God of War Ares, is her mentor. These changes to the core of the character have rankled many fans and some former writers as well. As in the late 1960s portrayal of the depowered Wonder Woman, this incarnation of the character saw both its supporters and detractors certain that they are correct in their reception of the character—some saw her as strong and heroic; others as weak and compromised.

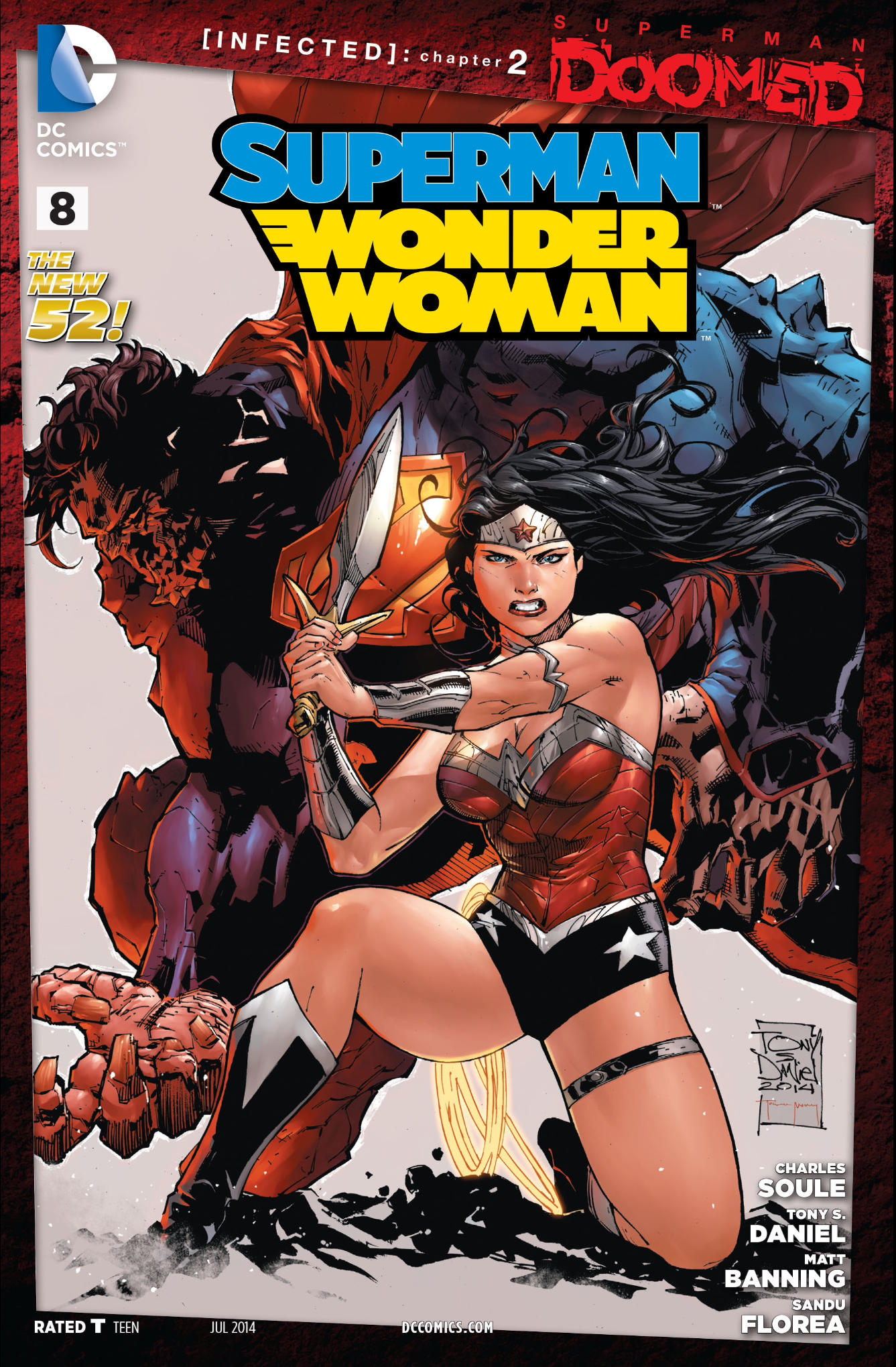

Based on the strong sales and reviews for this incarnation of the character, DC Comics launched a second title, called Sensation Comics after a comic from the 1940s in which the character starred. In general, these stories harken back to the more traditional portrayals of the character. A third simultaneous title, called Wonder Woman ’77 and based on the television show starring Lynda Carter, will debut in the spring. The character currently appears in Superman/Wonder Woman, and Justice League as well. In those two titles, the character’s curves along with her quickness to violence are emphasized; she is much more of a supporting character, and often the only female among males.

And just recently, a new artist and writer took over the main Wonder Woman title, David and Meredith Finch, respectively. Reviews have been mostly negative, criticizing the sexualization of the character as well as what seem to be out-of-character decisionmaking.

Why are there still so many different versions of this character? Well, answer many writers and editors, Wonder Woman is “tricky”. But it’s not the character that’s tricky. What’s tricky is that we live in an unequal world, a world where even the word ‘superheroine’ is considered to be a spelling mistake. If people were truly equal, a female superhero wouldn’t be tricky, because she wouldn’t be threatening or challenging to the social order through her very existence. She’d just be a superhero.

We just haven’t seen enough female superheroes in terms of either numbers or of different nationalities and sexualities and abilities, through whom we could more easily imagine that “anyone can be a hero.” Women have been historically underrepresented as characters in fiction across media—books for adults and children, comic books, live-action and animated television, live-action and animated film. They are much less likely to be represented as leaders or mentors, or as having a high-status profession. They are much more likely to be shown as interested in romance (with the “opposite” sex), more likely to be emotional or fearful, more likely to be slim and conventionally attractive.

This underrepresentation, this reliance on stereotypes, and this naturalization of inequalities are unacceptable. We need more females, and more female heroes, across media, depicting and circulating more diverse representations that open up the infinite possibilities of what heroism can look like.

Click here for the introduction to the Comics, Human Rights and Representation Week.

(This piece origina;;y published on February 2, 2015)