LUKE CAGE: HERO FOR HIRE

An appreciation/history by Bob Reyer

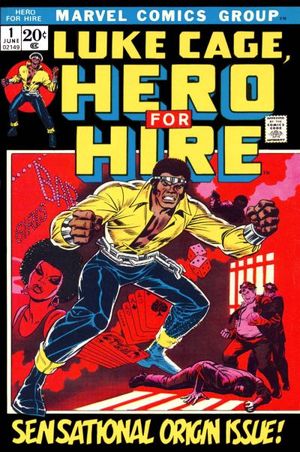

With the debut this week of the new Power Man & Iron Fist #1 by David F. Walker and Sanford Greene, a first issue that is rife with call-backs to the Seventies, I thought it high-time that I profess my love for Luke Cage, the “Hero for Hire”, a character who remains a favorite of mine more than forty years since his first appearance struck a chord in me that hasn’t stopped resonating.

(Not to slight Danny Rand, but as I did a run-down of his history for a Talking Comics podcast some while back, I’ll be focusing here on the original Luke Cage series, first sub-titled Hero for Hire, and then Power Man with issue #17. Perhaps one of you enterprising young-uns will take up the Iron Fist saga for your own piece?)

For some background, it was a much different comic book landscape back in 1972. The Silver Age was just giving way to the Bronze, and a new generation of creators was eager to build on the foundation established by Stan Lee, Jack Kirby, Steve Ditko, and the rest of the original Marvel Bullpen, that of characters who seemed to exist in a world much like our own, and who were, to quote Mr. Lee “heroes with flaws, but not flawed heroes”. These new writers and artists were adding extra layers of socio-political commentary to their stories, and with the revision to the Comics Code that took place in 1971, a more gritty realism was now possible, albeit still within what today would be seen as very strict guidelines.

In terms of diversity in comics, the first halting steps had begun a few years earlier, but while Stan Lee and Jack Kirby had debuted T’Challa, the Black Panther in Fantastic Four #52 in 1966, and Stan and Gene Colan introduced The Falcon in Captain America #117 in 1969 (who would achieve co-starring status in 1971’s issue #134), no African-American super-hero had top-lined their own title to that point.

Out in the real world, the burgeoning “Black Pride” movement that had arisen from the on-going struggle for civil rights was not only transforming the social fabric, but had also found expression in the entertainment media, most notably through the rise of “Blaxploitation” films. (As an aside, although there are many positive messages presented within those films, they also created or perpetuated some negative stereotypes, so it’s a dual-edged sword. Of course, how these messages are received is paramount.) Director Gordon Parks’ film version of “Shaft” that debuted in the Summer of 1971 is arguably the pinnacle of that genre, and is most certainly the antecedent that led directly to the creation of Luke Cage, Hero for Hire. (One can easily see Luke walking across Times Square from his office to John Shaft’s to trade information on cases!) Just a few short months after “Shaft” struck box-office and critical gold, there was this entry in the monthly “Stan’s Soapbox” Column:

The team assembled by Stan Lee to bring this character to four-color life was an interesting mix of veteran and newer talent; writer Archie Goodwin was doing great work on what was his first Marvel series, Iron Man, with Luke Cage’s iconic look created by John Romita, Sr., and even Stan’s right-hand man Roy Thomas pitched in some ideas. The series proper was begun under the pen of Mr. Goodwin, who for art duties tapped his Iron Man collaborator, veteran penciller George Tuska, whose “muscular” work was a great fit for the type of action the series would deliver. The third, and perhaps most important piece to this puzzle was inker Billy Graham, Jr., who would contribute inks, pencils, or covers to every issue under the “Hero for Hire” banner, and whose work defines the character of Luke Cage for many of us who were there at the beginning with him.

The team assembled by Stan Lee to bring this character to four-color life was an interesting mix of veteran and newer talent; writer Archie Goodwin was doing great work on what was his first Marvel series, Iron Man, with Luke Cage’s iconic look created by John Romita, Sr., and even Stan’s right-hand man Roy Thomas pitched in some ideas. The series proper was begun under the pen of Mr. Goodwin, who for art duties tapped his Iron Man collaborator, veteran penciller George Tuska, whose “muscular” work was a great fit for the type of action the series would deliver. The third, and perhaps most important piece to this puzzle was inker Billy Graham, Jr., who would contribute inks, pencils, or covers to every issue under the “Hero for Hire” banner, and whose work defines the character of Luke Cage for many of us who were there at the beginning with him.

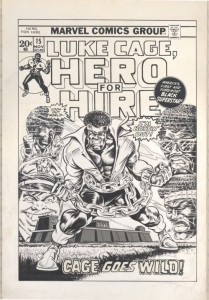

Mr. Graham, one of a handful of African-American artists working in comics at that time, came to Marvel after a stint at Warren Publishing where he worked as both artist and art director, before coming to the “House of Ideas” in 1972 as part of the team that launched Luke Cage. Of the original 16-issue Hero For Hire (the title changed to Luke Cage, Power Man with #17), he inked the debut issue over Mr. Tuska’s pencils, plus every subsequent one to follow (excepting #s 4, 6, and 16), as well as providing every cover after the second issue, and pencilling #4, #6, and #13–#16, and even co-wrote #14 and #16! (According to later series writer Steve Englehart, Mr. Graham was the virtual co-creator on their issues together, #5–#13!) I was and remain a big fan of Billy Graham’s work, with those covers enough to sell me on the series, but when those issues that he pencilled hit the news-stand–WOW! Mr. Graham’s dynamic style and gritty realism set the tone for the series, and his artwork on those early issues remains the high-water mark for the character of Luke Cage for me, even after all these years.

he inked the debut issue over Mr. Tuska’s pencils, plus every subsequent one to follow (excepting #s 4, 6, and 16), as well as providing every cover after the second issue, and pencilling #4, #6, and #13–#16, and even co-wrote #14 and #16! (According to later series writer Steve Englehart, Mr. Graham was the virtual co-creator on their issues together, #5–#13!) I was and remain a big fan of Billy Graham’s work, with those covers enough to sell me on the series, but when those issues that he pencilled hit the news-stand–WOW! Mr. Graham’s dynamic style and gritty realism set the tone for the series, and his artwork on those early issues remains the high-water mark for the character of Luke Cage for me, even after all these years.

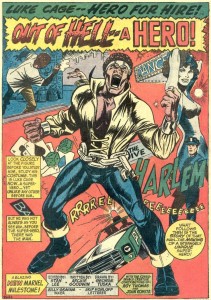

My association with Luke Cage began with that first issue seen above , which my Dad brought home from the stationery store one long-ago Thursday in 1972. (I still have that copy, too!) He was always on the look-out for #1 issues, and as we had seen and loved “Shaft” in the theatre, the cover caught his eye as something that melded that film’s sensibilities with super-heroics, and was he ever right!

The story opens on a scene in the inescapable Seagate Prison, where a man referred to only as Lucas has been incarcerated, sent to prison on a drug possession frame-up that we will learn was arranged by Willis Stryker, an old friend from the streets, angered over the loss of his girlfriend, Reva Connors, who had become Lucas’ fiancee. While in prison, Lucas discovers that Reva has been killed, shot by rival gang-members targeting Stryker, and he vows to avenge her death. Hoping for an early parole, he volunteers for an experiment in cellular regeneration conducted by Dr. Noah Burstein, who believes his story to be true.  When racist prison guard Albert Rackham, whose abuse of Lucas has caused his demotion from Captain, tries to silence him by disrupting the procedure, his interference causes Lucas immense pain, and he bursts from the experimental tank. He slaps Rackham, who crashes to the ground, unconscious. While Dr. Burstein tries to revive him, Lucas, fearing that he’ll be stuck in Seagate forever for killing the guard, punches the wall in frustration, only to find that he’s not damaged himself, but cracked the wall; he uses this new-found strength to literally punch his way through the prison walls, and escapes through a hail of ineffectual gunfire.

When racist prison guard Albert Rackham, whose abuse of Lucas has caused his demotion from Captain, tries to silence him by disrupting the procedure, his interference causes Lucas immense pain, and he bursts from the experimental tank. He slaps Rackham, who crashes to the ground, unconscious. While Dr. Burstein tries to revive him, Lucas, fearing that he’ll be stuck in Seagate forever for killing the guard, punches the wall in frustration, only to find that he’s not damaged himself, but cracked the wall; he uses this new-found strength to literally punch his way through the prison walls, and escapes through a hail of ineffectual gunfire.

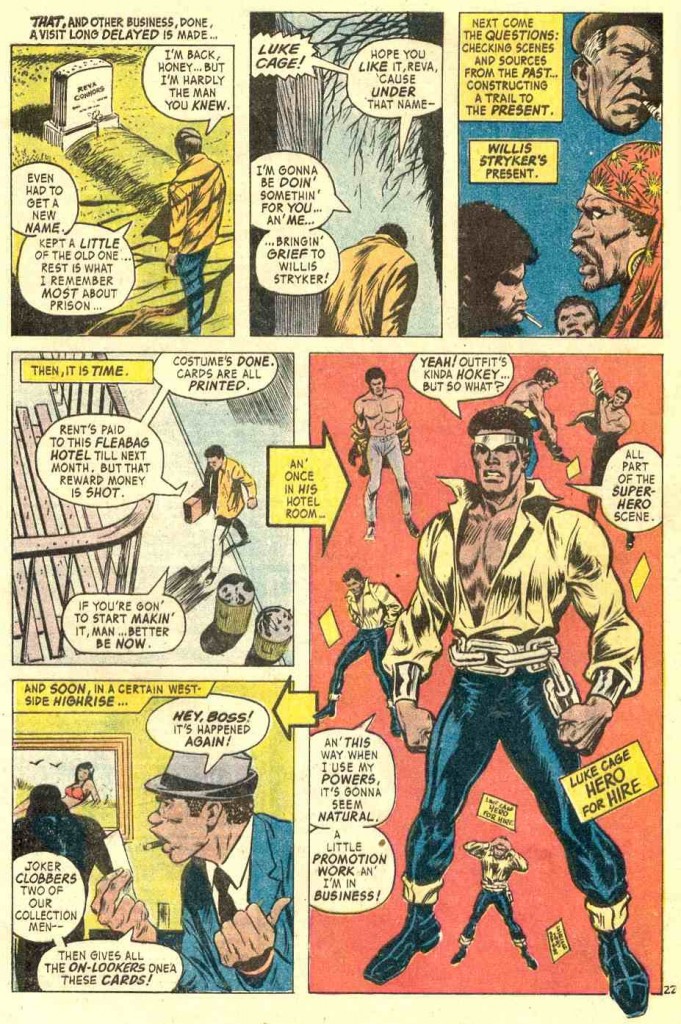

Back home in New York in search of Willis Stryker, Lucas muses that he has powers that he can’t use for fear of attracting attention, yet he nonetheless steps in and prevents the robbery of a local restaurant. When the owner gives him a cash reward for his bravery, it gives Lucas an idea for how he can sustain himself while on the hunt for the person responsible for Reva’s death. After creating an outfit from an escape artist’s props left behind in a costume shop (“Escape artist, huh? Tried somethin’ like that myself, I think I can dig it.”), Lucas visits Reva’s grave, and a new super-hero is born:

Luke Cage‘s origin tale would stretch into the second issue, which would introduce some of the long-running supporting cast, such as Gem Theater operator David “D.W.” Griffith and a character who would play a major role in Luke’s life, Dr. Claire Temple. The good doctor encounters Luke after he has a run-in with some of Willis Stryker’s henchman, and she marvels that he’s survived being shot at point-blank range. Bringing him to her clinic, the pair discover the place a shambles, busted up as part of a protection racket run by Willis Stryker (who, of course, is now a super-villain called “Diamondback”), with the clinic’s director injured, a doctor named Noah Burstein! Luke realizes that Dr. Burstein has recognized him from the prison, and fears that his new life, and his quest for vengeance for the death of Reva, may come to a very premature end. Obviously to us now (and then, too, frankly!), they didn’t, but it was a great moment, and one that presented the series with a thread that carried through many issues. As with nearly every other super-hero of the period, Luke Cage was always wary of his “secret identity” being compromised, but in his singular story, that exposure would send him back to prison. (As with the Blaxploitation films discussed earlier, that the only lead African-American super-hero is being threatened with prison, and this happening just as the draconian Rockefeller Drug Laws were about to be enacted in New York, can be seen as either an earnest attempt at social commentary about prison reform or the perpetuation of a stereotype, depending on reception.)

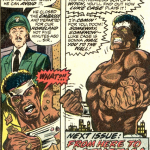

Archie Goodwin would only stay through #4, handing over the reins to Steve Englehart, who over his year-or-so at the helm would cement the traits that would define Luke Cage from there forward; certainly a street-tough brawler, but one who felt a duty and obligation to defend the people who had fallen below the radar of the super-hero population, and the possessor of a strong sense of personal honor and integrity. Mr. Englehart’s tenure would introduce characters destined for long runs such as lawyer “Big” Ben Donovan and gang-lord (gang-lady?) “Black” Mariah Dillard, but even though the book was mostly in its own world, when Mr. Englehart brought Luke Cage into the mainstream Marvel Universe, he did it with panache!

In issue #8 of Hero for Hire, Luke is hired by the agent for a businessman who will pay him $200 a day to find the men who have been stealing his employer’s technology. After a pitched battle in which Luke discovers that these industrial spies are actually robots, he seeks out his client, who turns out to be Doctor Doom! The Latverian monarch has hired Luke to retrieve his goods, as the robots had disguised themselves as black men, and so Doom thought it best to keep his own involvement a secret. (Luke: “Well, I don’t dig it…but you got a right to hire me like anyone else.”) Luke, distraught over having to destroy his mechanical foes to survive, returns to the Latverian Embassy to collect his fee, only to learn that Doctor Doom has closed the embassy and departed for home, never intending to pay!

returns to the Latverian Embassy to collect his fee, only to learn that Doctor Doom has closed the embassy and departed for home, never intending to pay!

Cut to issue #9, and Luke has gone to the Baxter Building and gotten Reed Richards to lend him a ship that can get him to Europe to collect his money, and so he sets off to confront Doctor Doom on his own turf. (“Latveria ain’t quite far enough to run!”). Cage gets involved in some strange political machinations involving space aliens trying to overthrow Doom’s reign, but at the end, it’s one-on-one between the Hero for Hire and the Lord of Latveria:

By early 1974, with increasing work-loads and decreasing sales a probable factor, first Steve Englehart and then Billy Graham, Jr. would leave the series, which Marvel would re-name Luke Cage, Power Man with issue #17, hoping that a more typical super-hero title (and story-line) would attract additional readers. I’ve been searching for the actual sales figures to no avail, but there is an answer to a letter in issue #21 that states that sales did go up with the title change.

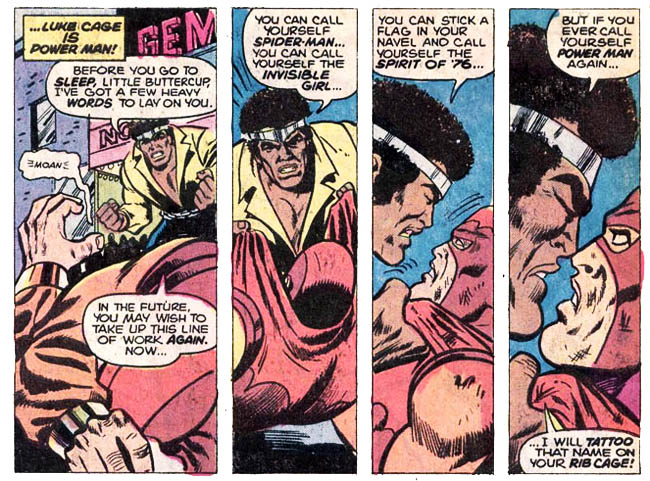

Speaking of Power Man #21, that October ’74 issue by writers Tony Isabella & Len Wein with art by Ron Wilson contains one of my all-time favorite pages. Erik Josten, the original, villainous Power Man (foe of the Avengers, and later member of the Thunderbolts) has come to New York City to reclaim his nom de super-heros from Luke. Whilst battling inside the Gem Theater, Josten makes the mistake of saying that the life of a little girl trapped inside with them doesn’t matter, which sends Cage into a fury, and he literally knocks Josten out of the building, leading to this classic Luke Cage moment, after which, he takes the little girl out for ice cream!

Marvel continued trying to grow the audience for this series by placing some of their best creative talent on board, adding Luke to The Defenders for a while starting in late 1974, and having him be the replacement for the de-powered Ben Grimm in Fantastic Four #168 , but none of those fixes took the series to a high spot on the sales chart. That all changed in late 1977, when someone at Marvel had the great idea of combining two faltering titles into something new. and put Chris Claremont and John Byrne to work.

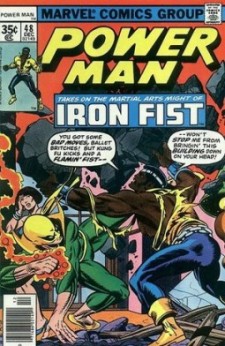

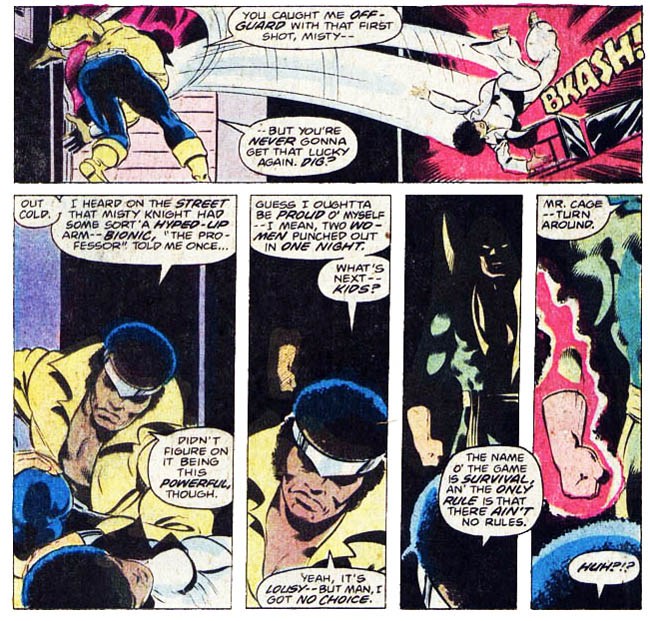

Messers Byrne and Claremont had been doing the Danny Rand solo book (and were just starting their epic run on X-Men that very same month!), so it was a seamless progression to have them be the team that merged Power Man and Iron Fist, and they came up with a great “meet cute”. In Power Man #48, we find Luke Cage running rampant through the West Side townhouse of Danny Rand, furiously in search of Misty Knight. He instead finds her partner Colleen Wing, who manages to get a call out to Misty before she’s accidentally kayoed by falling debris. Luke is tending to the unconscious Ms. Wing, when Misty bursts in, gun blazing. and with her bionic arm, manages to actually stun him before he subdues her as well, apparently under orders from an unknown master. In the next moment, comics history will be made:

A rumble ensues, and at the conclusion, after backing away from nearly killing Danny, Luke Cage, as beaten-down as we’ve ever seen him, states ruefully that “I’ve just killed the two people who’re the closest to me in all the world.”

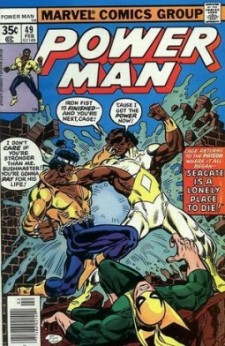

In the next issue (spoiler alert!) we learn that a super-villain named John Bushmaster (last seen in Iron Fist #15) has kidnapped Noah Burstein and Claire Temple, and to save their lives, Luke has been tasked with bringing Misty Knight to him so that he can exact revenge upon her. As a kicker, Bushmaster has proof that Cage was framed for the crime that sent him to prison, and he would have turned it over if Luke had completed his mission. The trio of Luke, Danny, and Misty head out to Seagate Prison to confront Bushmaster, where after an epic battle, Claire and Noah are saved, and Misty has retrieved the proof of Luke’s innocence.

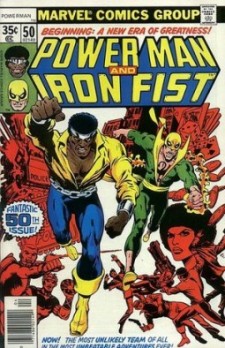

The book would be re-christened Power Man & Iron Fist with #50, with Chris Claremont  staying with the series until turning it over to Mary Jo Duffy with #56, and her 29 issue run would be the standard bearer for what readers remember so fondly about the team of Luke Cage and Danny Rand; the best kind of “buddy cop movie” chemistry, with an easy humour amongst all the high-concept action. The title would conclude with a bittersweet issue #125, although neither character would be gone for too long.

staying with the series until turning it over to Mary Jo Duffy with #56, and her 29 issue run would be the standard bearer for what readers remember so fondly about the team of Luke Cage and Danny Rand; the best kind of “buddy cop movie” chemistry, with an easy humour amongst all the high-concept action. The title would conclude with a bittersweet issue #125, although neither character would be gone for too long.

Through nearly all his iterations then, since, or now, Luke Cage as a character has carried a different burden than most; as the first African-American lead super-hero, there was the weight of being the flag-bearer for a race, and therefore any misstep or excess could be seen as offensive, or worse, the continuance of a negative stereotype, even if the usage of grittier elements were used in service of a story and character meant to be seen as a contrast to T’Challa, the elegant and highly-educated leader of a nation. As Adilifu Nama points out in his book“Super Black: American Pop Culture and Black Superheroes” (University of Texas Press/2011), he sees these characters through the lens of “…the multiple ideological permutations these black superheroes experienced as shifting symbolic expressions of political and cultural blackness…”, and finds it best to reflect on Luke Cage in a “critically celebratory” manner.

Whether a solo character, a part of a duo, a member of a super-team, or perhaps more importantly, as husband and father to Jessica and Danielle, in my mind, Luke Cage has epitomized the resolute defender of the downtrodden or forgotten, the last good man standing against those who oppress the people unable to fight back, and willing to take that battle from the street corners of New York City to the mystic realms. That he stands as such as an African-American super-hero whose origin lies in a corrupt and racist prison system adds a depth and radicalism to his narrative that I think transcends any negative attachment there might be to the trappings of the period in which he was born, granting him a place high on the list of the most important comic book super-heroes ever created.

ADDENDA

Luke Cage is #6 on my “All-Time Top 100 Super-Heroes” list.

I know that everyone’s favorite Luke quote is “Sweet Christmas!”, but he only began saying that about three years in; for we long-time fans, it’s “Sweet Sister!”

As you heard Bobby say on Quiz Night, comics fan and actor Nicholas Cage (nee Coppola) took his stage name from Luke Cage!

Soundtrack:

What else could it be but the Oscar-winning “Theme from Shaft”, as written and performed by Isaac Hayes:

[embedvideo id=”pFlsufZj9Fg” website=”youtube”]