Laura Sneddon is a comics journalist, writing for the mainstream UK press with a particular focus on women and feminism in comics. With an MLitt in Comic Studies, do not offend her chair leg of truth; it is wise and terrible. Her writing is indexed at comicbookgrrrl.com and procrastinated upon via @thalestral on Twitter.

Click here for the introduction to the Comics, Human Rights and Representation Week.

In recent years, “diversity” has become somewhat of a buzzword within the superhero comics industry and fandom, and a point of tension between life-long comic fans with a largely male online presence and newer fans from a range of different backgrounds eager to see themselves represented on the page. In many ways that tension has been eased – Marvel for example have committed to pushing several prominent female characters including the wonderful Kamala Khan as a newer, fresher Ms Marvel, and publishers certainly seem willing to listen to women fans. But after 12 months of constant drama within the comics community, from harassment campaigns to rape threats for female critics, it’s important to keep looking ahead as we acknowledge victories along the road.

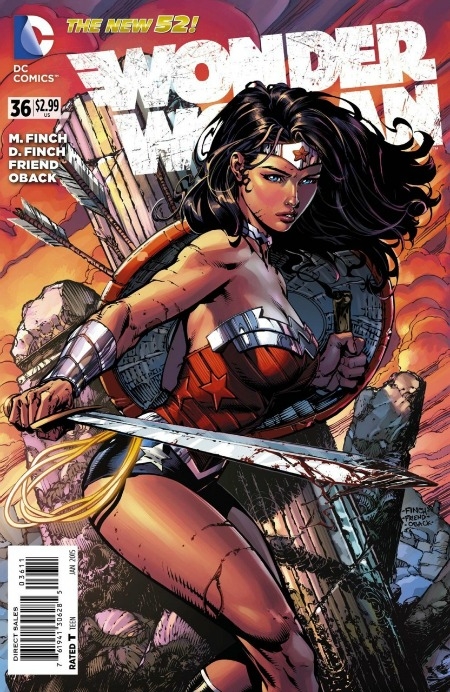

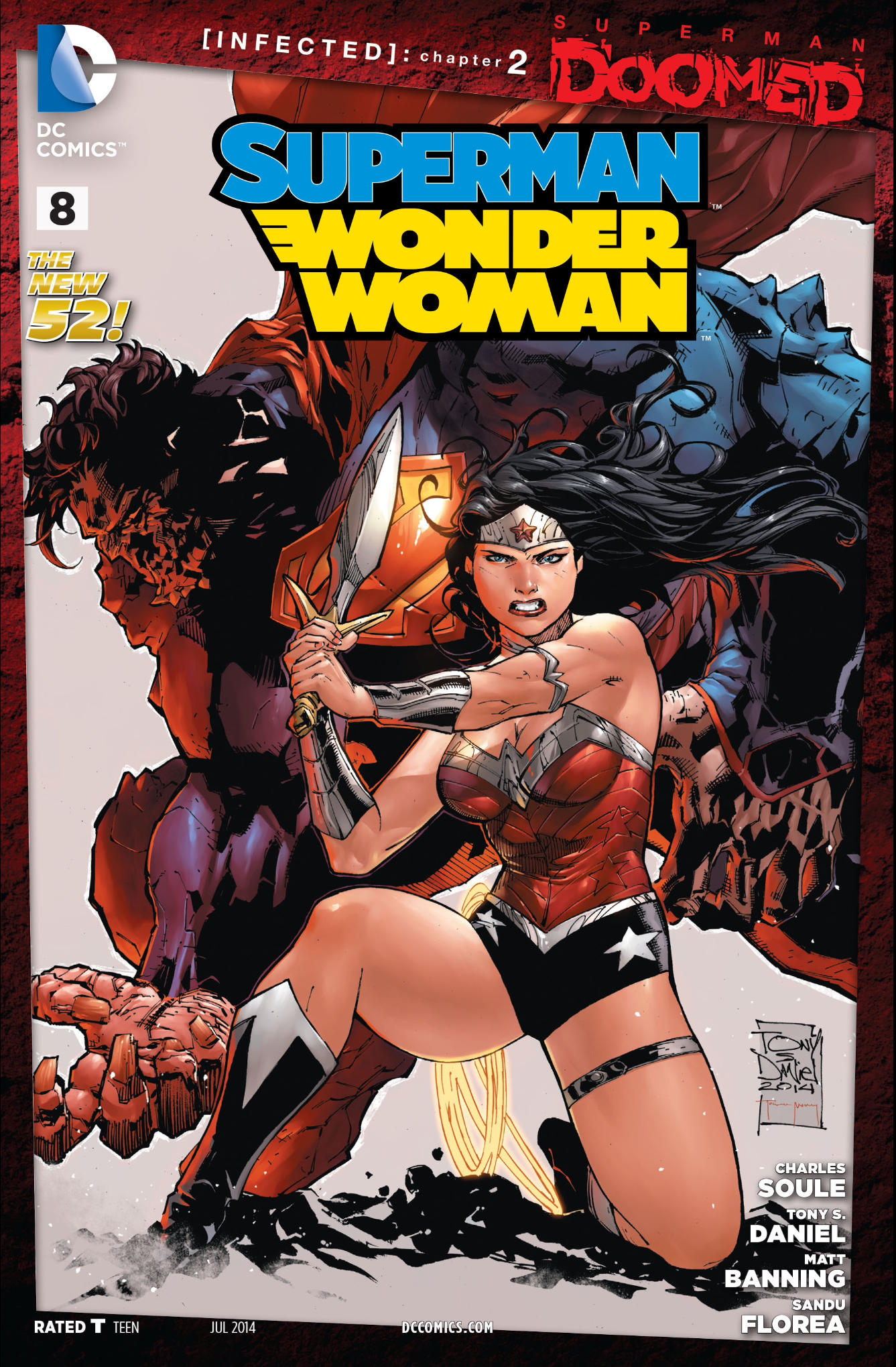

When I first began writing about comics back in 2011, the problems with sexism in superhero comics was something that I was determined to address. It soon became clear that this was an incredibly complex issue, and something that was going to get me – and other women – far more attention than I had anticipated. A piece on the seemingly controversial idea to place Wonder Woman in trousers rather than a skirt opened my eyes to a highly reactive segment of the comics community that decried any kind of change, an echo perhaps of the never-aging pantheon of superheroes that are constantly recycled and renewed.

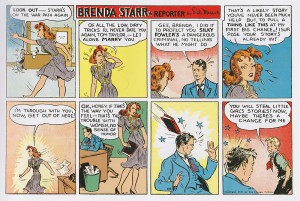

Digging into the history of Wonder Woman started me on a journey into the forgotten history of women in comics, and the many wonder women that came before Diana, both on and off the page; a forgotten history that very much ties into the tension within comics today. Before the appearance of Diana and her fabulous friend Etta Candy in the early ‘40s, there were a myriad of strong female heroes: the Phantom Lady, Sheena the Queen of the jungle, Torchy Brown, Brenda Starr, the Woman in Red, Fantomah, Miss Fury, and Red Tornado, the first female superhero, who disguised herself by wearing a cooking pot on her head (fashion!).

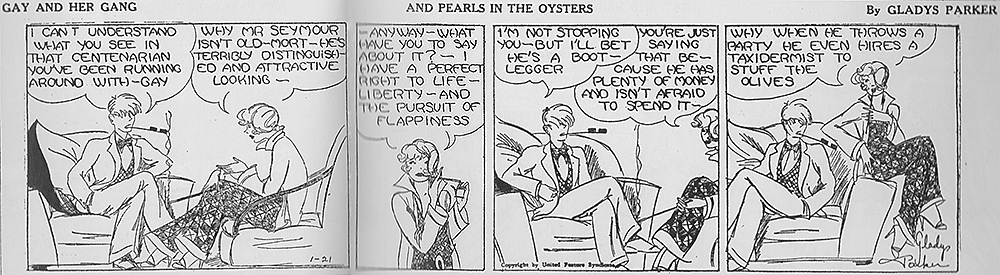

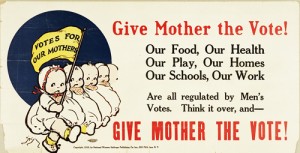

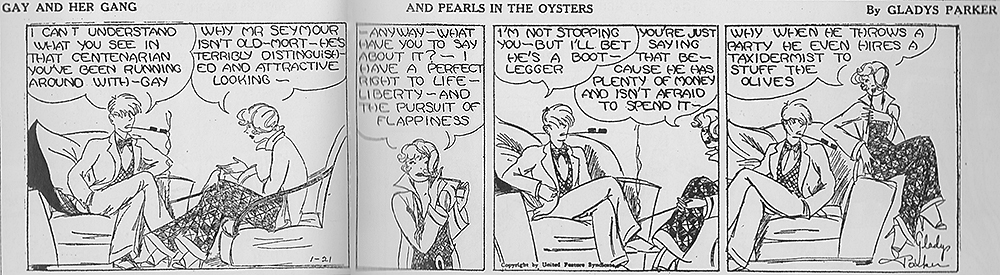

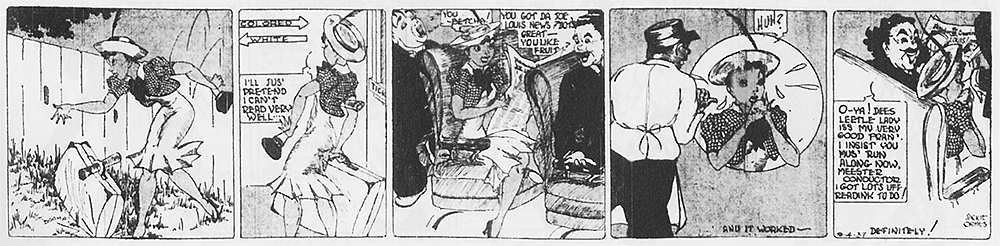

Female characters were abundant in all kinds of different comics, including the action genre that was to morph into the dominant superhero strain. Before and during the rise of the spandex clad heroes, newspaper comic strips were far more popular in the US and also had an abundance of female creators hitting it big: Rose O’Neill, creator of the Kewpies, published her first comic in 1896; Nell Brinkley was a major influence on many comic creators in her four decade reign working for Hearst’s newspaper empire; Kate Carew, investigative journalist, cartoonist and comics creator, debuted her first comic strip in 1902; Ethel Hays celebrated the roaring twenties with Flapper Fanny, later taken over by Gladys Parker; Dale Messick introduced readers to Brenda Starr, a strip that would run for some 71 years; Tarpé Mills created Miss Fury, one of the earliest (and most glamorous) costumed women in comics; and Jackie Ormes, the first African American woman cartoonist found great success with her Torchy Brown strips.

O’Neill and Brinkley were outspokenly supportive of the suffrage movement, in both their personal and professional lives, and contributed important pro-suffrage propaganda cartoons. Carew was known for her sharp political tongue, concocting a fictitious interview with the leader of an anti-suffrage league to ridicule them. Hays and Parker celebrated bold and independent women via their striking flapper strips. At the intersection of the ‘30s and ‘40s, Messick and Mills demonstrated that women were quite capable of creating action comics with genuine strong female characters. And Ormes infused her strips with racial commentary as well as gender politics, a radical accomplishment given her doubly reduced rights and visibility.

Mills’ cat, Peri-Purr, was included in her strips as Miss Fury’s cat, and the real life version became an honorary Admiral during the war. Carew cunningly scored a rare interview with the reclusive Mark Twain without his knowledge. Parker, also a Hollywood fashion designer, often portrayed her female characters in trousers, a huge leap forward for the portrayal of women in comics at that time. Ormes was investigated repeatedly by the FBI due to her membership of the NAACP, yet her overtly political comic strips flew under their radar.

These women are utterly fascinating, brilliant, and influential yet the vast majority of comic history books scarcely mention their names. And these are just a few of the many women forgotten from comics history – forgotten that is with the exception of the tremendous research carried out by underground comix legend Trina Robbins in bringing their works back into the light. Otherwise, the history of comics has been largely written by white men, and largely features white men. And this isn’t just the case in America.

The first major UK comic franchise predates much of what is regarded as early US comics history: Ally Sloper first appeared in 1867 before switching to his own dedicated comic, Ally Sloper’s Half Holiday, in 1884. Many history books list the creator as Charles H Ross, and mention his wife as a later artist. In fact Emilie de Tessier, who signed herself as Marie Duval, was a bona fide co-creator of Ally Sloper and one of the earliest known women to work in comics. Duval was one of four female contributors to Ross’ cartoon magazine of the time, which implies that women working in comics and as cartoonists were simply not that rare.

Shamefully de Tessier’s name was removed from reprints of Ally Sloper, her work has been regularly misattributed to her husband, and she was almost completely erased from comics history. (Even today some scholars insist Duval was simply an alias for Ross, despite their son speaking out to the contrary). Why is this so important? Not only are the women themselves forgotten from history, but their influence on their fellow artists – including men – is ignored.

The French de Tessier introduced stylistic choices never before seen in British comics, drawn from her influences in her native land, and the sheer popularity of Ally Sloper (far greater than any UK comics character today) positioned her as one of the most influential comic artists of her time. That influence, and that of the US women, is erased along with their names from the history books, with credit instead falling at the feet of the men who came after them. And lest we think this is a problem of the past, many of the incredibly ground-breaking storytelling techniques that writer Elaine Lee brought to Starstruck in the early ‘80s has been attributed to the later, male-written Watchmen.

These women are forgotten not due to lack of success or influence, but only for their gender. Many of these women experienced sexism (and in Ormes case racism too), and their position of the “other” in society makes their work of even greater cultural value. The fact that similarities can be drawn between, say, the work of Carew at the turn of the last century and the work of Kate Beaton today is remarkable given the lack of visible influential thread between them, in great contrast to the historical male creators that many will always point to as inspiration.

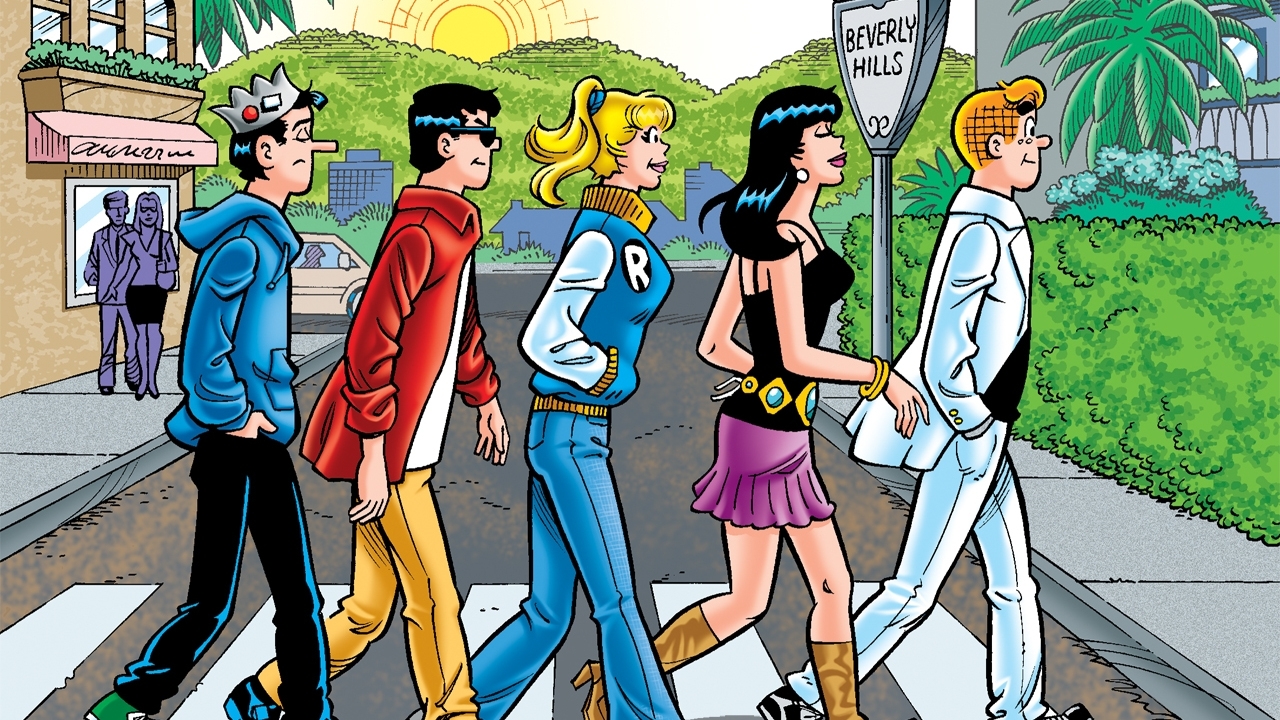

Newspaper comic strips, although ancient history to most, were the superhero comics of their day in terms of popularity within pop culture, though the sales were far, far greater. Indeed if we look outside DC and Marvel to the larger comics industry today, from graphic novels to independent comics to webcomics, we can see that women are still just as likely to be working in comics as men are.

Superhero comics are the exception. While superwomen are more prominent than ever on the page, and even get to have a slight variety of body shapes and skin colours, the creator line-up at DC and Marvel – while improving – is still struggling to match the rest of the industry. One reason for this is perhaps restricted access that comics only available in a comic shop maintain – while webcomics can be found by anyone and graphic novels are prominent in book shops, only someone deliberately looking for Super Captain Ballerina #3 is going to find it. Digital distribution has gone someway to challenge that – Ms Marvel’s digital sales in particular are testament to her popularity outside the regular superhero audience – figures are still ludicrously low in comparison to the number that pay to see superheroes beat up bad guys on the cinema screen or to be the Batman themselves in video games such as Arkham Asylum.

Superhero comics are still very much struggling to break free of their all-white, all-male, all-straight reputation. There may be fewer pendulous breasts on the covers, but they and their fellow direct market cousins have still got a long way to go. Let the past be a warning – we have been here before and things have gone terribly awry, independent female characters replaced with male-gaze fantasies and women creators forgotten. And shouldn’t we have more women of colour working in action comics than we did in the ‘30s?

Celebrate the victories, rejoice in Ms Marvel, celebrate diversity, but never feel embarrassed about asking for more!

Click here to read all of the Comics, Human Rights and Representation articles.

For more information on the early women in comics, pick up Pretty in Ink by Trina Robbins (or any of her earlier books), and Jackie Ormes: The First African American Woman Cartoonist by Nancy Goldstein.