The Red Diary

Written and Illustrated by Teddy Kristiansen

The Re[a]d Diary

Written by Steven T. Seagle, Illustrated by Teddy Kristiansen

Review by Joey Braccino

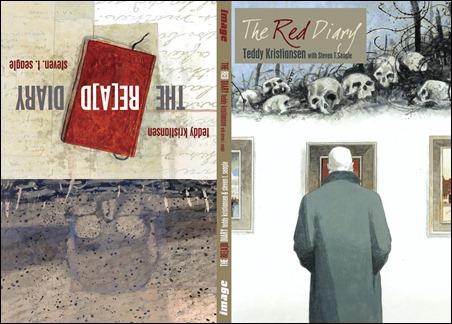

Teddy Kristiansen’s Le Carnet Rouge was actually published in French back in 2007 by Soleil Productions. Steven T. Seagle—American comics writer and Kristiansen’s collaborator on DC/Image’s acclaimed It’s A Bird graphic novel—received a copy of Kristiansen’s 65-page graphic “album” (those Europeans and their words!) and proposed the English translation that would become The Red Diary, released today by Image Comics. Seagle and Kristiansen’s final product is not a simple translation, but instead a profound experiment in artistic experimentation and storytelling; in Seagle’s own words, The Red Diary/The Re[a]d Diary is a project in transliteration.

The graphic novel released today contains two stories told using the same 65 pages of artwork. The first, The Red Diary, is an English translation of Teddy Kristiansen’s Le Carnet Rouge. The second, The Re[a]d Diary, is a “remixed” story, meaning that Steven Seagle took Kristiansen’s artwork from Le Carnet Rouge and filled in the word bubbles and caption boxes with an entirely new story. Furthermore, Seagle could not and cannot speak French (the text’s original language) or Danish (Kristiansen’s first language), so he actually wrote the story featured in The Re[a]d Diary without having read Kristiansen’s original. Instead, he relied on Kristiansen’s beautiful, expressionist artwork and some inventive visual translation to develop a new script.

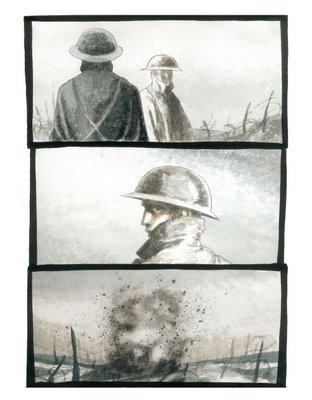

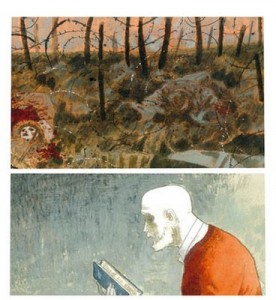

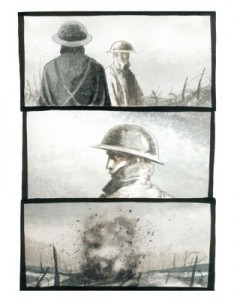

By the sheer whimsy of the universe, the two stories both explore the role of art in engaging and overcoming pain and despair. Kristiansen’s artwork splits the story between World War I Europe and (a) present. His work draws heavily from expressionist paintings from over a century ago, appropriate considering the time period explored. Kristiansen’s graphics evoke the despair, pain, and brutality of the Great War as well as the vibrancy and business of turn-of-the-century Paris and London. Because expressionism was the trend around 1900, the art rendered by the characters in the story are paralleled by the art rendered by Kristiansen himself. In this way, the metaphor of art as experiential and representative or the human experience is made literal. It’s stunning and a welcome change of pace from more traditional comics fare. I can see why Seagle was moved enough to want to bring this album of images over to American audiences.

For Kristiansen’s story, the reader is guided in the present by William Ackroyd, a writer grappling with the mystery of Phillip Marnham, a painter and soldier during World War I. As he uncovers a series of diaries—one red, one blue, one green—he discovers the painful story of a struggling artist, complete with drug addiction, money problems, and a violent benefactor. The painter, Phillip Marnham, eventually enlists in the army and dies in World War I. The devastation of Europe in World War I as well as the trauma that Marnham experiences both physically and emotionally pushes the narrator, Ackroyd, to consider his own life’s great loss (his wife, Marie) and the role art and the creation of art has in renewing, reviving, or simply continuing life in the face of despair.

For Seagle’s story, the reader is led to believe that William Ackroyd and the painter from the diaries are the same person, and that Ackroyd suffered memory loss during World War I and is reading the diaries to remember the life he had before the war. It’s an equally moving tale, and it also asks questions about realism and abstraction in art, life, and love. A twist revealed toward the end of the story pushes the question even further, asking how one can define his life by or live vicariously through someone else’s artwork.

The Red Diary is a profound piece of graphic literature. First of all, it’s about World War I—The Great War—which is an incredibly complex event in human history and incredibly under-represented in our cultural consciousness. Second of all, it’s own construction—particulary in the Re[a]d section—parallels its theme of the emotional, cross-generational resonance of art. Third, it’s simply beautiful to look at. Fourth, you get to look at it twice.

Verdict

Read it. Now. Both stories. Cover to cover. Pour over its imagery for hours. I did. Then go write/paint/draw/sing/do something. Anything.