by Nick Rocco Scalia

Everybody has that one holiday movie that, for one reason or another, holds a special place in his or her heart this time of year. Yours might be the one about the department-store Santa who turns out to be the real deal. Or, perhaps, it’s the one about the suicidal small-town guy whose guardian angel shows him how sad the world would be if he wasn’t in it. Or, very possibly, it’s the one about the bespectacled kid who desperately yearns for the one Christmas gift that will make his dreams come true, even at the risk of shooting his eye out.

Those are all great holiday stories, and it’s for good reason that they’re trotted out year after year for family movie get-togethers. But, for me, one film trumps them all, and when my loved ones gather to share our most cherished piece of Christmas cinema – as we’ve been doing every December for well over a decade now – we’re there to revel in the Yuletide cheer of a bloody, foul-mouthed, mayhem-filled movie that nevertheless has as big and warm a heart as any of the others.

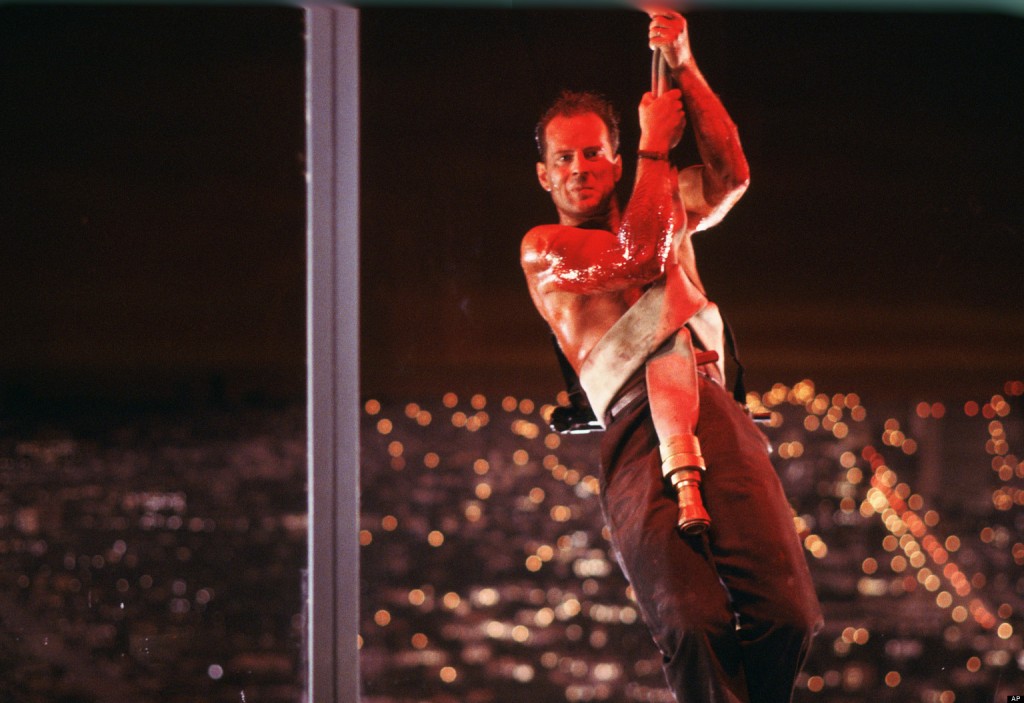

I’m talking, of course, about Die Hard, the franchise-spawning 1988 blockbuster that has solidified its stature among action movie fans as one of the very best films the rather disreputable genre has ever produced. If it’s somehow flown under your radar in the nearly 25 years since its release, here’s the short version: Bruce Willis plays John McClane, a wise cracking, hard-nosed NYC cop who arrives, jet-lagged and short-tempered, in Los Angeles to spend the Christmas holiday with his estranged wife Holly (Bonnie Bedelia) and their children. Holly has moved west to take a high-level position with a multinational conglomerate called the Nakatomi Corporation, and it’s at the company Christmas party that McClane makes his first awkward attempt at reconciliation. Unfortunately, his plans are interrupted when all manner of holiday hell breaks loose; a cadre of well-armed, well-funded terrorists led by the suave and ruthless Hans Gruber (Alan Rickman) forces its way into Nakatomi’s high-rise headquarters, takes all the employees hostage, and sets about breaking into the company’s generously stocked vault. As the only person in the building who manages to avoid being detained or killed, it’s up to McClane, caught barefooted and seriously outgunned, to outwit Gruber’s team of trained killers, free the hostages, and save the woman he loves.

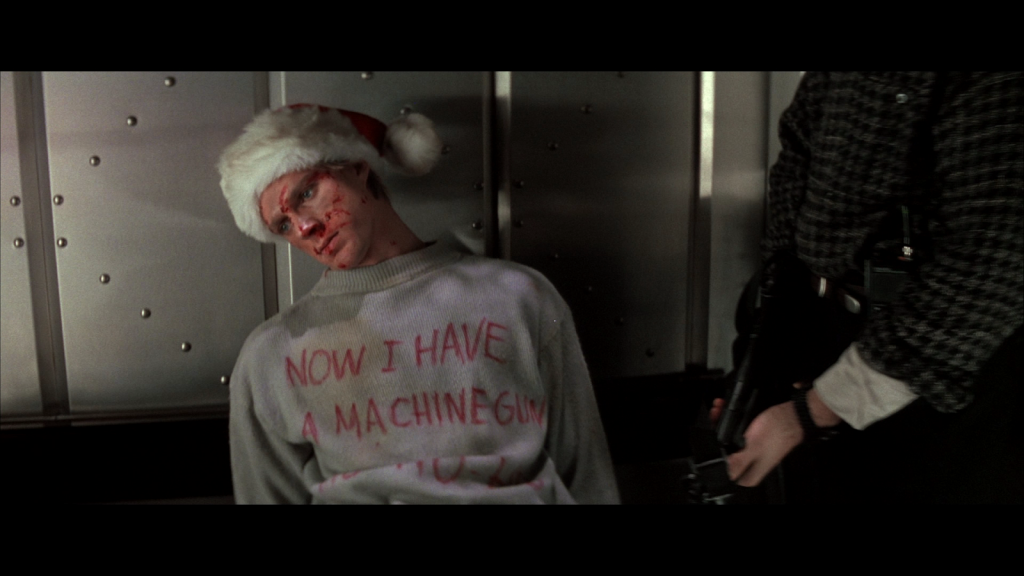

Zipping from one ingeniously choreographed action setpiece to the next, Die Hard doesn’t hide its holiday spirit – it’s there when McClane taunts his foes by slapping a Santa hat on a dead terrorist he’s offed (“Now I have a machine gun… Ho, ho, ho”), when Holly name-drops Rudolph and Frosty to thwart the advances of a lecherous coworker, and when Michael Kamen’s musical score quotes the jaunty melody of Winter Wonderland during an otherwise nail-biting moment. All of those elements, however, are just window dressing, clever but superficial little touches that could have worked just as well in any action movie set at Christmastime. The thing about Die Hard, though, is that it isn’t just an action movie set at Christmastime – it’s a traditional Christmas tale that, Uzis and f-bombs and explosions aside, is really just an amped-up variation on the very same themes that all the great holiday stories share.

For starters, just like A Christmas Carol – yes, I’m comparing Die Hard to Dickens, so deal with it – the film rails against selfishness and greed, underlining the point by being set during what’s supposed to be the season of giving. Gruber’s bunch of bad guys turn out to be not terrorists but thieves, interested in stealing Nakatomi’s assets for themselves rather than using them to advance a political cause; meanwhile, the company plots billion-dollar deals and third-world construction projects while its executives indulge in coke-sniffing and casual sex at the office Christmas party. In stark contrast, our hero spends nearly the entire movie barefoot and clad in a soot- and sweat-stained undershirt, fighting it out in a state-of-the-art skyscraper with thugs who wear expensive European suits and pack all manner of high-tech hardware. McClane emerges as nothing less than a butt-kicking Bob Crachit, a blue-collar guy struggling to do right by his family no matter the cost. There’s a character like him at the heart of every good Christmas story – one for whom wealth and material things are meaningless, and whose only holiday wish is the safety, happiness, and comfort of his loved ones.

And then, of course, there’s the John-and-Holly subplot, the strained-yet-sweet romance that provides the film’s emotional core. Whereas women in eighties action movies tended to be little more than pretty-looking cardboard cutouts, Holly is smart, tough, and tender in equal measure (her presence has been sorely missed in the film’s most recent sequels), and as viewers, we’re just as invested in whether or not the McClanes will be able to save their marriage as we are in whether John will be able to defeat the baddies and save the day. That’s a neat trick for an action flick to pull, and even better, it serves as a pretty effective reminder of one of the things that the Christmas season is all about: putting aside our differences and stopping to appreciate the people who mean the most to us. When John, bloodied, bruised, and battered almost beyond recognition, finally finds Holly at the end of the film – he greets his wife with a comically apologetic “Hi, honey” as Gruber menaces her at gunpoint – it’s a legitimately heartwarming reunion, and even though there’s still more carnage to come, for a brief, beautiful moment, all is calm and all is bright.

Finally, what really resonates in Die Hard is the notion of sacrifice. Smarter people than me have viewed McClane as something like a Christ figure, and while that might be pushing things a little far, there is an almost spiritual quality to his selflessness and suffering over the course of the film – from beat-downs to broken glass to stale Twinkies, he willingly bears what no man should ever have to, and as the film’s title implies, there’s no amount of pain or danger or adversity that he’ll allow to stop him from doing so. In a more secular sense, Die Hard’s hero is essentially just enduring a violently exaggerated version of what a lot of us do during the holiday season: we run ourselves ragged, enduring endless stressful shopping days, malfunctioning Christmas lights, empty wallets, overtime hours at work, and an infinite variety of other holiday hassles just to make sure that those we care about can have a merry Christmas.

Ultimately, McClane is the kind of noble, giving, unselfish person that this season of love and generosity inspires us all to be, and that’s probably why there’s such a transcendently joyous quality to the film’s closing scene: John and Holly embrace in a limousine and ride off to spend a happy holiday with their children, scraps of debris drift down like snowflakes to the cheerful strains of Vaughn Monroe’s “Let it Snow, Let it Snow,” and just like on that first Christmas Eve a long time ago, the world has found itself a new savior – peace on earth, goodwill to men, yippie-ki-yay motherfuckers.