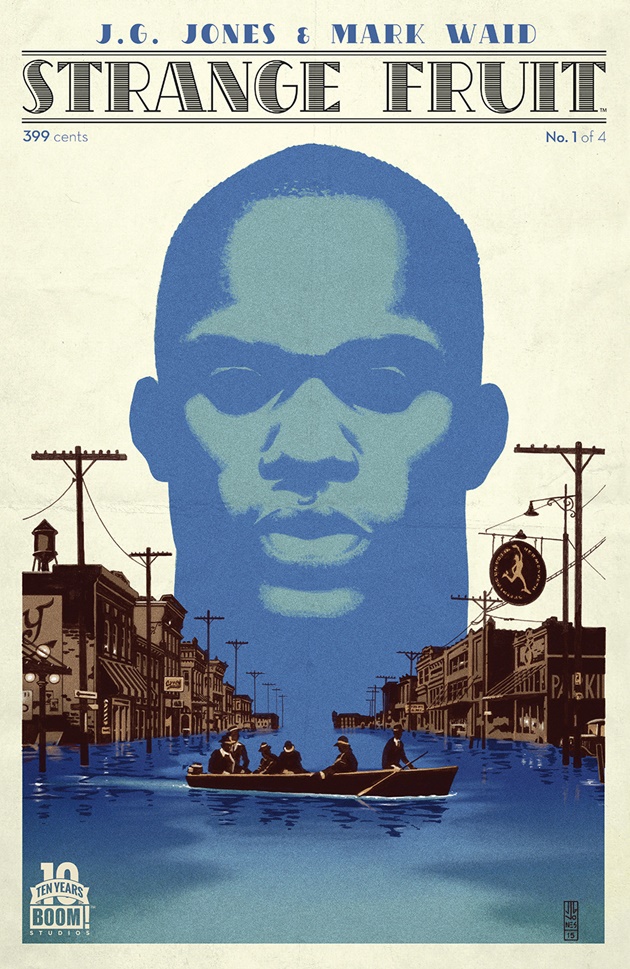

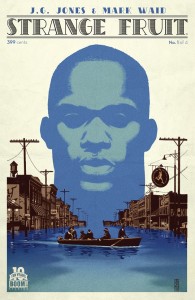

Strange Fruit #1 (of 4)

Storytellers – J.G. Jones & Mark Waid

Art – J.G. Jones

Lettering – Deron Bennett

Editor – Ian Brill

Review by Joey Braccino

At first glance, Strange Fruit is a promising, intriguing book. The premise—an exploration of racial and class conflicts in the Mississippi delta during the great floods of 1927 WITH some Twilight Zone-esque sci-fi mixed in—is at once startling relevant and classic comics genre-bending. The creative team brings together two industry greats in Mark Waid and JG Jones. The publisher, BOOM! Studios, has been on fire over the last year or so with creator-driven hit after hit.

So for all intents and purposes, Strange Fruit should work, which makes it all the more a pity that it really, really doesn’t.

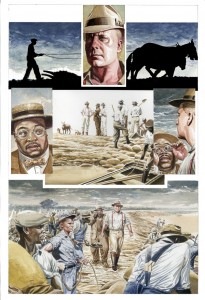

Again, the premise is super socially relevant right now given our current conversations regarding race and racism in our country. Waid and Jones are clearly interested in exploring the issue of racism in this period drama, starting with the evocative title (an anachronistic allusion to the poem and song of the same name from the late ‘30s that eerily illustrates the aftermath of a lynching). The first issue is loaded with situations grounded in the intersection of racism and class in the South in the 1920s. With the floodwaters rising, white Southerners are anxious to shore up levees and find someone to blame; both desires are satisfied with the “Bucks”—the derogatory term for Black men. A White character claims that the flood is especially bad this generation because there are “too many n*****s ‘round here wearin’ suits and not enough fillin’ sandbags.” The casual (and constant) use of derogatory racial slurs is meant to evoke the time period and establish just how terrible the racial strata was (and is), but there really isn’t any effort past that to draw any of the characters—White or Black—as anything other than cardboard cut-outs from any clichéd film on Southern bigotry.

Which, of course, is shocking given the caliber of the storytellers here. Mark Waid’s recent hotstreak in comics has been rooted in his ability to mix on-point dialogue with spot-on characterization. Here, he really doesn’t hit either all too well. Apart from the “lead” character—a Black man named Sonny who is accused of stealing—there really aren’t any clearly defined figures in the book. A slew of men and women enter and exit the panels, but most are left unnamed or are too terribly clichéd to really make any impact. The dialogue is equally ineffective in propelling any narrative. The plot really takes off when a mysterious spacecraft crashlands into the dam, releasing a strange figure that plays at the racial issues at the core of the book. It’s an intriguing sci-fi slant on an otherwise straightforward period piece, but it’s a little too out there given the historical grounding of the previous 15 pages. And, considering the social commentary inherent to the subject matter, the sci-fi angle seems a bit distracting and derivative.

The final panel will be particularly provocative given the recent events regarding the Confederate flag. There is something extraordinarily subversive about it, sure, but it still feels a bit problematic and, to some extent, unnecessary.

With all this said, I do need to applaud JG Jones for the stunning artwork. Jones’ painted illustrations feel like a Norman Rockwell painting in their representation of American life. Combine those Rockwell portraits with Alex Ross’ work on Marvels and you’ve got the gorgeous aesthetic of Strange Fruit. I wonder what it would have been like to read this book without any of the shoddy word bubbles (and overly digitized lettering) and haphazard dialogue. The visual experience is so engrossing and evocative that I almost wish it were a silent comic.

Verdict

SKIP. I suppose Strange Fruit #1 should be applauded for its ambition to tell a social justice story set during the Great Mississippi floods of 1927, but the execution is unfortunately terribly ineffective. Gorgeous artwork aside, the attempts at subversion, racial and class commentary, and genre-bending fall completely flat.