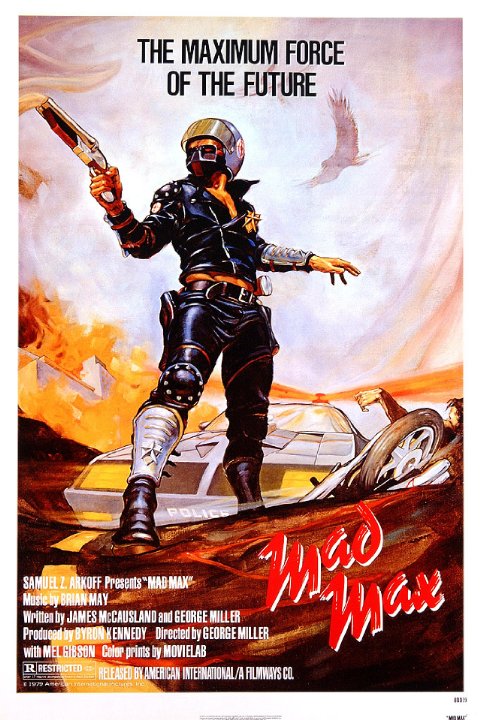

Mad Max: An Action Movie Out of Time

by Nick Rocco Scalia

Two souped-up muscle cars locked into a collision course on a strip of burned-out Australian outback highway – a high-speed battle of horsepower and suicidal bravado between a steely-eyed hero and his raving, psychotic nemesis that only one of them, and only if he’s damn lucky, can possibly survive.

Such is the climax of Mad Max‘s opening sequence, an almost unbearably tense modernization of the archetypal high-noon Western standoff that, three-and-a-half decades on from its creation, hasn’t lost a shred of its power to set pulses racing. This is action cinema breathtakingly stripped down to its barest essentials: a hero, a villain, a head-to-head confrontation, and maybe most importantly, a sense of real, tangible danger as this clash of men and machines hurtles toward its inevitably explosive conclusion.

And yet, as perfectly realized as that moment might be, it’s fair to say that Mad Max is far from a perfect film overall. Director George Miller’s feature debut is uneven in the way that many of the low-budget crash-and-smash “car-sploitation” pictures that inspired it were, and likely for the same reason: unable to afford wall-to-wall stunts and destruction, the filmmakers had to fill in sizable gaps between action scenes with whatever they could find to pad the movies to feature length. Max does a better job of this than most, thanks to Miller’s unique and well-realized vision of a world slowly but surely spiraling out of order – not yet “post-apocalyptic” but most definitely “pre-apocalyptic” – and the towering, star-making screen presence of young Mel Gibson as the titular hero.

But still, Mad Max‘s pacing is rather slack, its final battle not entirely satisfying, and its human drama – good cop loses everything, casts aside the law to take revenge – is undeniably formulaic (though rendered somewhat more interesting by the fact that the entire world, not just Max himself, has been teetering on the brink of chaos throughout). Nevertheless, the film transcends its flaws largely on the strength of its tremendous on-road action sequences, brilliantly choreographed, possessed of a furious energy, and captured in an immersive style that combines rushing, bat-out-of-hell tracking shots with wide-angle compositions that solidly establish spatial relationships and, thus, immeasurably elevate the vehicular confrontations’ impact thanks to their absolute clarity.

Those scenes, with their beautifully realized stuntwork and destruction, represent something of a lost art in action cinema. One of the greatest pleasures of Mad Max is the understanding that we’re seeing real cars (and motorcycles and vans and other vehicles) driven by real people, and they’re really trading paint, crashing, exploding, flying off the road, and so on. Miller does a fantastic job of building tension – even the off-road scenes, such as the first encounter between Max’s wife and the villainous Toecutter, are infused with menace – and his action setpieces are fueled by the incredible sense of peril that can only be achieved by putting actual flesh and blood and metal on screen. On a subconscious level, the knowledge that people actually risked their lives to accomplish what we see makes the movie that much more exciting, and this is perfectly accentuated by Miller’s style, which relies as little as possible on post-production trickery to depict all of this mayhem – the film instead prefers to let us observe it unfolding in all of its catastrophic glory, usually cutting away only to get a better look at all the carnage.

Of course, this isn’t to say that there’s anything particularly wrong with modern, CGI-driven action cinema. It’s just that those films’ priorities and intentions are entirely different from those of something like Mad Max. Movies like the Fast and the Furious series – and even the last two Die Hard installments – derive their appeal from their characters’ seeming invincibility, their capability to override the laws of physics and the all-too-breakable nature of the human body* in sequences that achieve increasingly bombastic levels of spectacle. Anything is possible in these films because CGI can make anything look possible; combine that with lightning-quick editing and handheld camerawork, which can strategically leverage what we don’t see in order to make us believe (or, at least, suspend our disbelief), and you’ve got a perfect delivery system for impossible feats and colossal-sized shenanigans. The end result is, essentially, superhero movies without the superheroes, and considering that some of their biggest box office competitors are actual superhero movies, it’s easy to see why action films had to evolve in the way they have.

In sharp contrast, however, Mad Max repeatedly emphasizes just how vulnerable its characters actually are. We, as viewers, are not meant to cheer them on as they plow through their opponents and laugh incredulously as they survive each hare-brained exploit. Instead, we’re meant to fear for Max’s life as he charges at full speed into an all-but-unavoidable collision with the Night Rider; we’re meant to feel the impact when Goose is thrown from his motorcycle and crash-lands in the dirt. That’s an awfully big difference from the (admittedly enjoyable) sequence in Fast Five in which Vin Diesel and Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson smash each other through a series of plate-glass windows, metal cages, and cinder-block walls for what seems like a good ten minutes of screen time, then shake it off seconds later. Mad Max‘s thrills might be less spectacular, but they’re also a lot less safe – the consequences seem real and the pain is palpable. The movie itself may not be as “larger-than-life” as a modern action blockbuster, but even so, its characters’ go-for-broke brashness in the face of their physical fragility – and, in turn, that of the filmmakers, throwing caution to the wind and every last scraped-together dollar of their budget on the screen – makes it seem so much riskier and tougher and gutsier than anything we’ve seen in such a very long time.**

Bottom line: Mad Max is not only a great movie but an important one, a film that can proudly stand alongside everything from Stagecoach to Bullitt to Die Hard in the annals of action-cinema history. And while it’s easy to think we’ll never see its likes again, along comes none other than George Miller to deliver the long-overdue sequel Mad Max: Fury Road, reportedly a two-hour car-chase extravaganza constructed of practical effects and stunts, shot on location in the Australian desert once again. Like Mad Max himself, the movie is a loner – courageous, perhaps insanely so – in a world that has moved on. But with its foot on the gas and its eyes on the road – the real road, the one on which fuel and flesh and fire are thrillingly alive rather than artificial – it’ll survive.

*I feel a little uncomfortable making this point in light of Fast star Paul Walker’s death; I can’t think of a more tragic example of life not imitating art.

**All of this applies, in a rather exponential way, to The Road Warrior as well. Didn’t want to neglect to mention it.