Wonder Woman: Wonder Words

Some correspondence answered by Bob Reyer

(That letter above is from 1974’s Wonder Woman #212, commenting on the return of the Amazons and Diana’s super-powers.)

With some heightened attention of late regarding Wonder Woman, I’ve recently had some letters and Forum posts seeking my counsel on where to begin reading her adventures, how to get acquainted with the various eras of her history (“her-story”?), how she has been portrayed through the years, and also a question regarding one of the more controversial and debated topics from her early years.

(Might I remind you Robert, that you also received a few calling for your resignation; don’t forget those, darling! @udrey)

(Well, that is true Audrey, but I’m not here to talk about letters from my family, friends, and co-hosts, so let’s move on, shall we?)

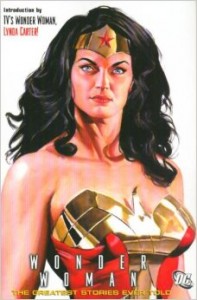

The flood started with a lovely letter from Michelle, who expressed interest in helping a friend get started reading the comic book tales of Wonder Woman (and whose only exposure to the Amazon Princess had been the Lynda Carter TV show); with Michelle’s own readings on the character limited she didn’t want to steer her friend wrong. This “reading list” request was followed almost immediately by this note from David, that covered similar ground…but added a kicker:

I’m a recent comic book reading convert and I’ve been a listener to the Talking Comics podcast for over a year now. One of the things that has fascinated me is your strong opinion of Wonder Woman and how she’s been portrayed. I heard the episode with Gail Simone and Greg Rucka and your view sounded very informed, but I never got a feel for how it was created. What stories and/or authors built the essence of what Wonder Woman represents to you and what is that essence? I ask because I’m really interested in reading the title but I don’t know what to seek out and what to avoid, also I was chatting with an employee at my comic store and she had said that she enjoyed the Azzarello WW and that the earlier stories weren’t all that people say it is due to the creator’s use of bondage imagery and themes.

David

As you’ve all heard, I’m quite passionate about Wonder Woman, and rightly so, as she is, without question in my mind, the most important super-heroine ever created. So, when I feel that Diana is being “miss-treated” by her corporate handlers, or ill-served by creative teams, I take umbrage. When Wonder Woman is presented to best advantage, she represents something far beyond the usual super-heroics as an aspirational figure, striving to see good in all people, and herself emblematic of the strength that compassion can generate. The Amazon Princess came to “Man’s World” on a mission to help keep the world safe from fascism, but despite her physical prowess, she was also an ambassador for peace, with violence her last resort, a philosophy codified by Gail Simone with this quote from Diana in her story from issue #25 “A Star in the Heavens: Personal Effects” :

“We have a saying, my people. ‘Don’t kill if you can wound, don’t wound if you can subdue, don’t subdue if you can pacify, and don’t raise your hand at all until you’ve first extended it'”

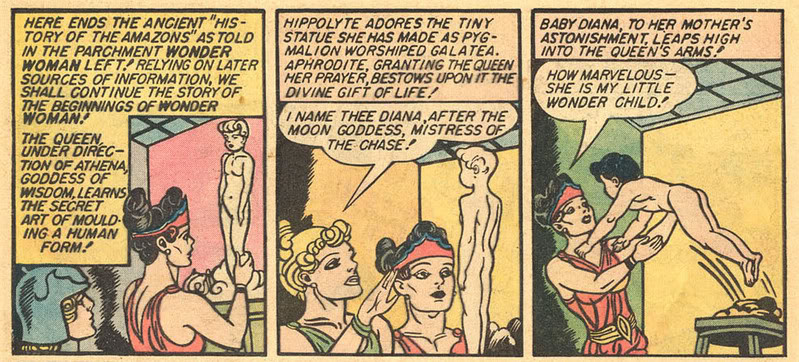

As many long-time fans of Wonder Woman do, I have some problems with the current depiction of the character as the “God of War” by Brian Azzarello (not Cliff Chiang though, the art is quite nice!), when her message was historically one of peace. A greater affront may be the changing of her origin from a mother’s longing to have a child, a heart-wrenching desire that results in a goddess-driven miracle birth, where now Diana is the product of a one-night-stand which wholly removes the emotional depth from what might be comics’ most poignant origin sequence. Beyond that, Mr. Azzarello’s characterization of the Amazons as harpies willing to hijack and murder sailors in order to have children might be more accurate to the Greek Myths in some ways, but is certainly not what her creator had in mind!

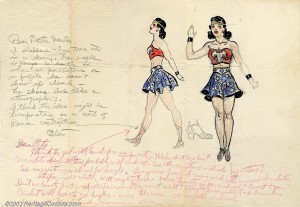

Wonder Woman was created in 1941 by a psychologist, Dr. William Moulton Marston, who decried comics’ “blood-curdling masculinity” in a magazine article which led to a conversation with All-American Comics publisher Max Gaines about creating a super-powered female character. Dr. Marston believed that women had un-tapped potential for leadership, in that they were as strong and capable as men, but that their strength was tempered with compassion, and in a New York Times article, predicted a coming matriarchy! With artist Harry G. Peter on board, he set out to create a character that would be someone for young girls to emulate, and for young boys to see as an example of the true power of the modern woman.

Wonder Woman was certainly capable in the super-heroic sense, but in her triumphs over villainy, she more-often-than-not brought the captured evil-doers to Paradise Island to be rehabilitated, displaying a compassionate wisdom far beyond the norm in comics at the time. The Amazons themselves were not the blood-thirsty warriors of Greek myth (nor Mr. Azzarello’s stories!), but a race of women who retreated to a place safe from the distrust, hatred, and violence in “Man’s World”, and in doing so, created a technologically-advanced haven where their culture flourished. Even so, when apprised of a threat to the freedom of people everywhere, Queen Hippolyta sent her only daughter out into the larger world to help spread their philosophies; an act of true altruism, and one that set the tone for Dr. Marston’s Amazons throughout his years at the helm.

To address David’s friend’s concerns about some of the imagery in these early stories, she is correct in saying that there are many panels depicting Wonder Woman in various states of…”distress”, shall we say, but as in virtually every instance she escapes or triumphs solely through her own intelligence, courage, or gifts, I think it clear that Dr. Marston was using those images to instruct readers in his ideas of women not needing to be “rescued”, but that given fair opportunity were quite able to forge their own way through adversity. This is especially cogent considering that many of the themes in these images were influenced by artwork from the Women’s Suffrage Era, a period where Mr. Peter worked at Judge Magazine alongside pioneering cartoonist Annie Lucasta “Lou” Rogers.

Mr. Hanley’s book is fascinating (and recommended), but whilst there is quite a bit of new information there, as well as some interesting mathematical studies of the early stories and art, the post-Crisis Modern Era is torn through in less words than is contained in one of our Talking Comics essays on the subject, and I’ve yet to come across an in-text reference to the controversial New 52 re-boot, so it falls a little short of being a complete history, but is a great read nonetheless. There is much about Robert Kanigher and his “domestication” of Wonder Woman in the post-Marston Fifties and Sixties, and a bit about Denny O’Neil’s de-powered “Emma Peel” era, but the author does spend the first section on the early years, particularly Dr. Marston and his philosophies, with a focus on (hence the title?) his apparent fascination for B&D imagery as a means to show submission. Mr. Hanley, in a later section, takes the feminists of the Seventies to task for ignoring the seemingly conflicting nature of Dr. Marston’s messages caused by their inclusion in those stories, asserting that they “glossed over the more problematic bits of the character and focused on the areas that reflected their own modern feminist beliefs. Their version of Wonder Woman restored parts of the original, but ultimately they re-created Wonder Woman in their own image for a new generation.”

I don’t wholly disagree, but as Mr. Hanley goes on, there is a certain clucking “Tsk, tsk, ladies” quality to his discussion of that era that troubles me, and despite goodly amounts of verbiage on radical and liberal feminism, and references to the important Second Wave Feminist books “The Second Sex” by Simone Beauvoir and “The First Sex” by Elizabeth Gould Davis, I’m not certain that on this issue he stands completely with these women who dared so much in a very different world than our own. He makes a case that in compiling the stories for the “Ms. Collection” hardcover in 1972 that they picked ones that reflected their own feminist values, and not in the same balance as Dr. Marston’s original intent. Maybe it’s me, but as I read this section I can’t help but feel that Mr. Hanley, in trying to “catch the ladies out”, has actually missed a different point about how readers might perceive what seems the glaring contradiction in the Golden Age stories of Marston & Peter.

I certainly don’t pretend to speak for everyone, but as long as we’re not discussing true sadism or brutality, if two consenting adults wish to practice role-play in their relationship, that’s up to them. If Dr. Marston was a “bondage connoisseur” (as Mr. Hanley states it), and therefore utilized specific terms or had Mr. Peter illustrate panels in a particular way (almost always to show Wonder Woman triumphing over adversity!), was this much different than the war comics of the period being accurate about military hardware, a fashionista artist being specific about the cut of a dress, or more recently, Steve Ditko espousing Ayn Rand, often verbatim? Couldn’t it be more likely that the women and men who embraced Wonder Woman as a feminist icon in the Seventies simply had a more accepting view of the good Doctor’s peccadillos and instead focused on the broader message, as opposed to what Mr. Hanley seems to feel was a conscious decision to white-wash them?

One could argue that as literature for children, these images could create confusion, sexual tension, or perhaps the chance moment from which a fetish begins, but I would counter that their usage went over the heads of young readers (as has been pointed out by our frequent guest, comics “her-storian” Trina Robbins, who read them in their original release!), as would their inclusion in the movie serials and adventure films of the time that were also aimed at them, but that the larger themes did impact positively on those to whom those messages were intended. Did the message get mis-read by some? Absolutely, but do we then homogenize everything that might be layered in order to make it safe for every audience, at every second, particularly considering the overwhelmingly positive response this character has generated among women, men, and children over three-quarters of a century?

Of more recent vintage, my list would include the one-shots Wonder Woman: Spirit of Truth by Paul Dini and Alex Ross, The Hiketeia by Greg Rucka and J.G. Jones, and the charming Wonder Woman Adventures Special.

As to reading longer swaths in the modern era, both Greg Rucka in 2003 through 2006 (#195–#226) and Gail Simone in 2008 through 2010 (#14–#44) did fine work throughout their runs and are excellent reads, but the gold standard is the George Perez Post-Crisis re-boot, and the two trades “Gods and Mortals” and “Challenge of the Gods” will give you a great reading experience! Not far behind is Phil Jimenez’s work, and highly recommended would be the issues collected in “Paradise Lost” (#164–#170) and “Paradise Found” (#171–#177). I would also recommend the “Wonder Woman” animated film, which was very well done, excepting a bad line-or-two of dialogue!

ADDENDA: Here’s an interesting conundrum; despite many critics opining that Wonder Woman is “difficult to get right”, there have been far more good or great runs over the last 25 years than bad ones!

ps) I’ll attach two articles detailing Wonder Woman’s creation and history, as well as a link to our “Wonder Woman Round-table” podcast, that might be of help: